How much should you understand and how much should you know? It’s the eternal question of opening preparation! Ideally, you should understand everything and thus need to know nothing. Unfortunately, you need to know something before you can understand. So you first need to know, then understand, and then you should forget what you know and leave only understanding? But will you still understand if you no longer know?

I don’t normally write sentences like that, but they describe my perplexity when going deeper into an attacking line I shared in my article from the game Mariotti-Beliavsky Leningrad 1977 last week. The line in question arose after

1.d4 Nf6 2.Bg5 d5 3.Nd2 Nbd7 4.Ngf3 h6 5.Bh4 e6 6.e3 c5 7.Bd3 Be7 8.c3 0–0 9.0–0 b6 10.Ne5 Bb7 11.f4

and now the inferior line

11…c4 12.Bc2 b5

So, if you had asked me a few weeks ago to assess the position I would have said categorically that White is much better. Pressed further to clarify this grandmasterly insight, I would have pointed to 2 factors:

- The fact that Black has released the central tension with …c4, giving White a free hand on the kingside.

- The more subtle point that Black has played the move …h6 which makes it harder to drive a knight away from e5 with a pawn as …f6 can be met by Ng6 (as …h6 has weakened Black’s control of g6)

In principle, that’s a correct assessment of the position and comes some way to matching the engine’s 2.26 (after days of analysis)

Now an interesting point however. According to the engines there is just one move that realises that 2.26 evaluation, whereas the next 2 moves in its list only achieve 0.66 and 0.64. Let me confess that the first move I would focus on (13.Qf3) is not in that top 3. Let me also confess that if – after analysis – I had decided that the engines’ top move was necessary, I would see it as a slight defeat and adjust my assessment of the position downwards a little!

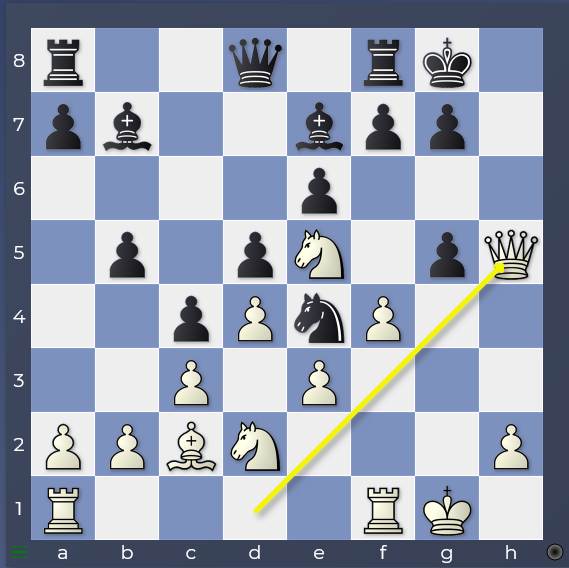

The key line is the surprising 13.Bxf6 Nxf6 14.g4

and then the essential follow-up 14…Ne4 15.g5

Let’s just go back first of all to why 13.Bxf6 is surprising to me. There are several reasons:

- In the opening I met 4…h6 with 5.Bh4, so it feels odd to play Bxf6 now. I know that circumstances change, but the urge for consistency and efficiency is very strong!

- Giving up a bishop for a knight is an unnatural way for me to start off an attack: I strongly associate bishops with attacks!

- Exchanging off a set of minor pieces before launching an attack also feels odd: my instinctive reaction is keep as many pieces on as possible while attacking (to have material in reserve to sacrifice later!)

- Black’s position looks cramped after 12…b5, with minor pieces clustered together on the second rank. Exchanges seem to help Black free his position. Bear in mind also that Black played 12…b5 to protect …c4 and make a future …Ne4 exchanging minor pieces possible. Why would I be doing Black’s job for him?

That’s a lot of inner prejudices to overcome! The only way I would consider 13.Bxf6 would be after failing to make my main idea of 13.Qf3 work to my satisfaction.

It’s not a bad move (the engines rate it as about 0.5) but it does allow Black to play the freeing 13…Ne4

when after 14.Bxe7 Nxd2! I have to play the inefficient retreat 15.Qd1 Qxe7 16.Qxd2.

The engines still assess this as slightly better for White which is fair enough but I would be very dissatisfied with this result from Black’s “huge” strategical mistake 11…c4. I’d also unequivocally reject a line involving 13.Qf3 and then the retreat 15.Qd1 on aesthetic grounds! So what I might do then is to start considering 13.Bxf6 Nxf6 14.Qf3

In this way, I get my queen to f3 which is both a good attacking square and prevents Black from plugging the b1-h7 diagonal with …Ne4 (at least not without losing a pawn). And this would give me a platform for launching my kingside attack with g4-g5. The engines gives this idea 0.99 which is a clear advantage, though obviously not optimal either.

So it’s interesting to consider what my initial “understanding” of the position gave me: a good assessment of the position, and possibly a path to a good but not optimal continuation (13.Bxf6 Nxf6 14.Qf3) However, I have to confess that I wouldn’t be confident of always finding this line. If I were in poor form, I might easily skip past it. And of course. The “understanding” of the position I had by “default” (basically the fruit of all my years playing chess!) was certainly not enough to get me to the best continuation.

Why am I going on all the time about “understanding” and “not wanting to know anything”? Well, opening theory is so huge nowadays, it’s easy to be overwhelmed by what book authors think you need to know (i.e. the specific lines you need to remember) in order to play just one line. Multiply that 15 or 20 times for a complete repertoire for Black and White and you are setting yourself up for a ceaseless diet of opening line revision that will eat up all your time for chess study. Surely the ideal should be to understand chess – or more narrowly, the opening positions you play – so well that you don’t need to memorise anything specific: you are capable of working out the best lines and you are able to do so consistently. I truly believe that this should be the holy grail for every chess player – both professionals and amateurs. However, it’s not always easy to work out what that understanding looks like! So let’s give it a go here!

What sort of understanding would I need to be able to find the plan of 13.Bxf6 Nxf6 14.g4 (ignoring Black’s ability to play …Ne4) Ne4 15.g5? Well let’s see what the critical variation is: why does this line actually work for White? Well obviously you might think about 15…hxg5 and now White plays 16.Qh5

Obviously 16…Nxd2 allows 17.Qh7+ mate but what about 16…g6? That blocks the b1-h7 diagonal with tempo and threatens to capture the knight on d2. Well 17.Nxg6 fxg6 18.Qxg6+ Kh8 and now 19.Rf3 g4 (desperately hoping to use the tactic 20.Qxg4 Rg8 to plug the black kingside) 20.Bxe4 dxe4 21.Qh5+ Kg8 22.Qxg4+

is killing because the black king can’t escape with 22…Kf7 due to 23.Qh5+. Finishing off is always more complicated for a human player than an engine, but with enough time you would make it!

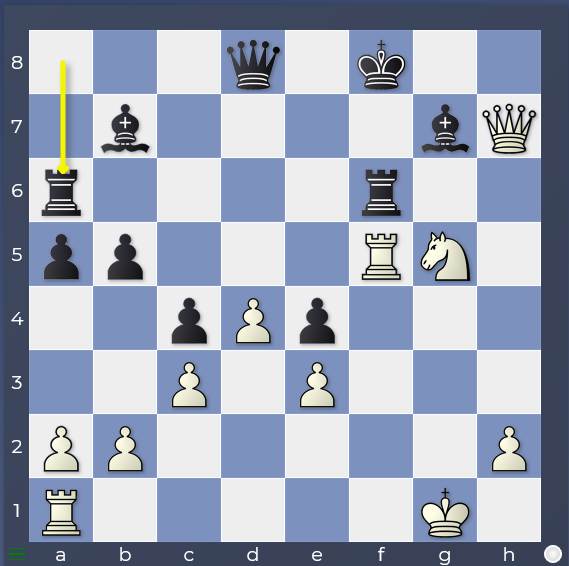

16…g6 tends a little towards the suicidal, but what about a sensible move like 16…Bf6?

Black is maybe threatening …g6 now as his bishop can retreat to g7 after Nxg6 …fxg6, Qxg6+ to cover the black king. At the same time, Black is threatening …Bxe5 to swap off a white attacking piece possibly followed by ….f6. Calculating at the board I wouldn’t be very sure whether 17.Rf3 g6 18.Nxg6 fxg6 19.Qxg6+ Bg7 20.Rh3 Rf6 21.Qh7+ Kf8

is really objectively good for me as I’m not attacking with an enormous amount of pieces. Actually, the engines consider it losing for White! (-1.30!)

The actual key engine main line is 17.Ndf3

17…g6 18.Nxg6 fxg6 19.Qxg6+ Bg7 20.Bxe4 dxe4 21.Nxg5 Rf6 22.Qh7+ Kf8 23.f5

If I saw this line during the game, I would definitely believe it! Instead of a rook on h3 and knight on d2 as in the previous line with 17.Rf3, I have a knight on g5 in the mix and a rook on the soon-to-be-opened f-file.

So should I be trying to draw out general patterns and ideas from these variations after 13.Bxf6 Nxf6 14.g4 Ne4 15.g5 and internalise them as part of my understanding of this variation? So that if I reached this position or a similar one in a game 6 months later I would be able to work out the variations myself despite not having any memory of the concrete variations I had seen before?

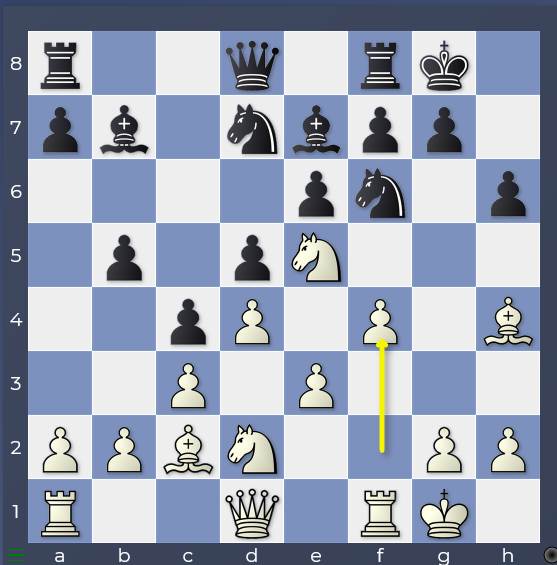

Well, it never does any harm to spend time studying positions in this depth, but the key question is whether such a set of variations is generalisable. Out of curiosity, I played around with my engine on a superior version of this line for Black. Instead of Black playing …b6 and …Bb7 and then later …c4 and …b5, Black plays …c4 and …b5 immediately, saving a tempo: 9…c4

10.Bc2 b5 11.Ne5 Bb7 12.f4

So in this position, it’s now Black to move. If you read my first article, you’d only be looking at 12…Ne4 which is definitely the best move. But I was vaguely wondering how my engine evaluation would jump if I played some vaguely useful but also useless move. For example, 12…a5 supporting the…b4 push a little more.

So I stare at my engine evaluation and it’s barely moving. I feel like giving it a kick or something but it stays around 0.40. After some exploration, I discovered the reason:

13.Bxf6 Nxf6 14.g4 Ne4 15.g5 hxg5 16.Qh5 Bf6 17.Ndf3 g6 18.Nxg6 fxg6 19.Qxg6+ Bg7 20.Bxe4 dxe4 21.Nxg5 Rf6 22.Qh7+ Kf8 23.f5 exf5 24.Rxf5

All as we know so far (watch out for the threat of Ne6+!), but now with the extra move 12…a5, we have the miracle defence

24…Raa6

reinforcing the rook on f6 while covering the e6-square which the engines assess as 0.00! Just a small insignificant difference – a pawn move on the queenside! – makes a difference of 5 pawns in the evaluation!

Looking back on this experience, it made me think that there were 3 clear levels of “understanding” for this position.

The first level was for this position (13th move, White to play):

You understand the general evaluation of the position – VERY good for White – and generally why:

- …c4 released the central tension early and

- Black was unable to follow up quickly with …Ne4 to block the b1-h7 diagonal because his c4-pawn would have been loose.

The second level of understanding enables you to find this continuation: 13.Bxf6 Nxf6 14.Qf3

You understand that

- Black’s key plan was to play …Ne4 to block the b1-h7 diagonal

- It’s important for White to restrain this plan and that giving up the bishop pair to achieve this is a good trade

- White’s follow-up plan is to launch forwards the kingside pawns with g4-g5 supported by Rf2-g2 for example.

The third level of understanding enables you to find this plan 13.Bxf6 Nxf6 14.g4

and the correct response to 14…Ne4 which is a pawn sacrifice with 15.g5 hxg5 16.Qh5

The engines are also fighting against Black’s plan of …Ne4, but in their own much more sophisticated way! But you also need understanding of the tactical motifs – attacking and defensive – to make this level of understanding practically useful.

And what I wonder is whether this third level of understanding is worth striving for! For human players, this level of understanding enters the realm of brilliancy and fantasy and it’s not something that we can achieve consistently. Whereas the second level of understanding definitely is something we can aspire to and execute with a high degree of certainty.

So what I’m thinking about is how to develop an opening repertoire supported by the right level of understanding that minimises the specific lines you need to remember to achieve a consistently high level of play. And note I’m certainly not talking about just playing boring lines with nothing in them for either side: I’m talking about a way of approaching every type of opening to achieve this goal. I certainly think that achieving this requires accepting that your understanding of the position does not need to be the perfect one. You need to accept that a level of understanding above your own exists – a place you might even venture into on the odd occasion when the force is with you! – but that is most likely a place you do not need to be to achieve practical success.

I have a long held belief that levels of understanding are critical to optimising one’s decisions. Your excellent article reinforces this and I will seek to apply your concepts to my search for an effective opening repertory. Using the …c4 push in these lines to explain your thoughts was inspired.

Thanks Blair! Hope it helps! 🙂