In 1932, Bogoljubov and Spielmann played a 10-game match in Semmering, Austria which Spielmann edged 5,5-4,5. In his biography of Bogoljubov, Soloviov is dismissive of the match, stating “…after [Bogoljubov] won the first two games, he failed to press home a huge advantage in the third game and then he blundered a piece in game 4. Later he almost completely lost interest in the match, because it was more or less an exhibition event” I wonder what the source for this assertion is because just looking at the games, the match looks hard-fought and entertaining! Spielmann included 2 of his wins in his classic “The Art of Sacrifice” (and Karsten Muller included a 3rd in his recent expanded edition of this book for Russell Enterprises) so he obviously felt he’d played pretty well!

The second game of the match won by Bogoljubov was a tense affair in which the game turned when Spielmann reacted passively to Bogoljubov’s risky play. I haven’t analysed this game exhaustively, but rather focused on a few moments that interested me. Readers of my recent book “Chess for Life” (co-authored with WIM Natasha Regan) will recognise the pawn structure in the game as the Carlsbad pawn structure. We examined this structure in great detail in one of our chapters on the English GM and 2014 European Senior Champion Keith Arkell. We saw there how Keith – through judicious exchanges of minor pieces – leaves his opponents with only a dark-squared bishop against his knight and then launches a minority attack against Black’s queenside. The resulting weak pawn on the light square c6 cannot be defended by the dark-squared bishop which inevitably falls (and the d5 pawn after it). In this game Bogoljubov pursues a similar light-square strategy, but in this case focused against Black’s kingside light-squares

Bogoljubov,Efim – Spielmann,Rudolf

Semmering 2nd Match game 1932

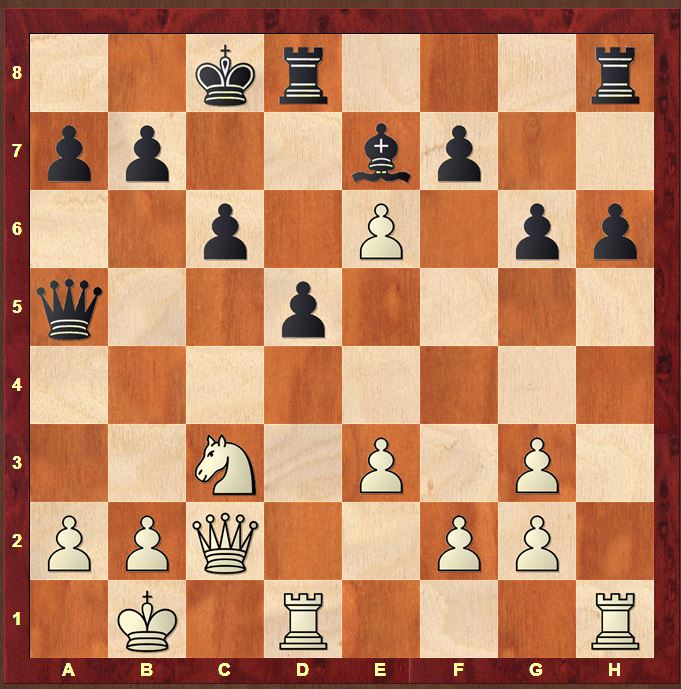

1.d4 e6 2.c4 Nf6 3.Nc3 d5 4.Nf3 Nbd7 5.cxd5 exd5 6.Bf4 c6 7.e3 Be7 8.Bd3 Nh5 9.Bg3 Nxg3 10.hxg3 Nf6 11.Qc2 h6 12.0–0–0 Qa5 13.Kb1 Bg4 14.Bf5 g6 15.Bxg4 Nxg4 16.Ne5 Nxe5 17.dxe5 0–0–0

17…Bb4 18.e6 Bxc3 19.exf7+ Kxf7 20.bxc3 is given as equal by Soloviov, but that seems rather dubious to me: the Black king’s position is flimsy and both White rooks can join in the attack via the 4th rank.

18.e6

After 18…fxe6 19.Qxg6

Black loses a pawn – either e6 or h6. Maybe it’s just me, but I was quite surprised by this turn of events. Both Black and White have been making grand gestures: White has castled queenside, Black has brought out his queen threateningly to a5, Black has pinned the knight on f3, White has prevented Black from castling with Bf5… and in the end the position gets reduced to the small area e6–h6, an area in which after 18…fxe6 19.Qxe6, Black for all the material at his disposal – a queen, 2 rooks, a bishop, 6 pawns and a king – cannot protect 2 pawns, or even create some noteworthy counterplay to distract White’s attention! Of course, the essence of the position is the weakness of Black’s kingside light-squares (in particular the pawn on g6) and it’s interesting to note how many factors have contributed towards this:

- It started with Black’s manoeuvre …Nh5xg3 which netted the bishop pair but opened the attack of the rook on h1 on the pawn on h7 (which the just exchanged knight on f6 was no longer defending).

Note that Keith always plays an early Bg5xf6 to exchange his bishop for the knight as soon as possible:

8.Bxf6 Bxf6 9.Bd3

- White then exerted further pressure on the b1–g6 diagonal and the h7 pawn with Bd3 & Qc2. This forced the weakness …h6, weakening the g6 square.

- The Black queen moved to a5, far away from the protection of the kingside light squares.

- White exchanged off the light-squared bishops with Bf5. This tempted a Black pawn to g6, where it is protected only by the pawn on f7.

We saw this move Bf5 a number of times in “Chess for Life” – both Keith and Karpov played it! For example, take the game Karpov-Campora from the 1994 match in San Nicolas:

20.Bf5

- The exchange Ne5 …Nxe5, de created a lever with which to mine the f7 square (and thus undermine the g6 pawn) with e5–e6. It also exchanged the last Black minor piece capable of defending the light squares and left Bogolyubow with the desired minor piece balance of knight vs dark-squared bishop

18.e6 is the start of a series of undermining pawn breaks (18.e6, 19.g4, 22.e4) that seek to wipe away Black’s pawn occupation (and control) of the central light-squares. For all this, I’m not sure that Black is objectively worse in this position: his position remains basically sound. However, the continuing series of blows to his position add up to a difficult practical challenge.

18…f5 19.g4

A further consequence of Black’s manoeuvre …Nh5xg3: White gains an extra g-pawn to undermine Black’s kingside while …Rhf8 is prevented due to the open h-file (White’s attack on the h-pawn) Note that not only does White force entry into Black’s kingside light-squares, he also removes the restraint Black was exerting on White’s e4 break.

19…fxg4 20.Qxg6 Rdg8 21.Qc2

Threatening Nxd5

21…Kb8 22.e4

White continues his assault on Black’s light squares.

22…d4 23.Ne2

A risky and ambitious attempt from White

23.Rxd4 Qe5 24.Rhd1 Qxe6 25.f4 gxf3 26.gxf3

is given by Soloviov as a slight edge for White. I wasn’t very sure about this, but the more I looked at it, the more I liked White’s chances.

26…Rd8 27.Qh2+ Ka8 28.Qc7 Rc8 (28…Rxd4 29.Rxd4 Rc8 30.Qd7 Qxd7 31.Rxd7 Re8 32.f4 Kb8 33.e5 Kc8 34.Rd3) 29.Qd7 Qxd7 30.Rxd7

I was thinking about why White should put in so much effort (Qh2–c7–d7) to exchange off queens. My feeling is that only in this way can White emphasise the difference in the mobility of the White and Black kings. White will establish his pawns on f4 and e5, protecting f4 with a knight on e2 and blocking Black’s passed h-pawn with a rook on h3 if necessary. His king will then be free to move to e4 to shepherd the White kingside pawns home. Black’s king in comparison has little hope of activity. It’s not hopeless for Black, but I like White’s chances of making something of this. Take the following sample line:

30…Bg5 31.Ne2 Rhf8 32.R1d3 (32.Nd4 intending Nf5 is another idea) 32…h5 33.Rh7 Rh8 34.Rxh8 Rxh8 35.f4 Bd8 36.Rh3 h4 37.Kc2 Kb8 38.e5 Kc7 39.Kd3 Kd7 40.Ke4

Anyway, back to the game and Bogoljubov’s risky 23.Ne2

23…c5 24.f4

This surprised me a great deal when I saw it. It’s certainly logical for White to mobilise his kingside pawns and try to link up with his advanced pawn on e6 with f4–f5. However, White’s position feels loose and overextended: the pawn on e6 is still far from the rest of White’s forces after 24…gxf3 25.gxf3, while the newly-opened g-file is all Black’s to exploit.

24…gxf3 25.gxf3

25…Qa6

A logical move, attacking e6 at once and preventing Qc4 but it allows White to deploy his pieces freely after which the advantage swings his way again. However, Black could set White greater problems by pinning the White knight with

25…Rg2

Time for a little bit of concrete analysis:

a) 26.Rdg1 Rf2

The rook is even better on f2 than on g2 as Black now also threatens the simple …Rxf3 in addition to …Qa6 hitting the knight on e2 and loose pawn on e6. (26…Rxg1+ 27.Rxg1 Qa6 28.Nf4 Qd6 was Soloviov’s line, but 29.Nd5 Qxe6 30.Rg7 looks like good play for the pawn)

27.Rg7

27.Rf1 Rxf1+ 28.Rxf1 Qa6 is a much stronger version of the game as White cannot even cover the e6 pawn with Nf4 due to the hanging rook on f1; 27.Qc4 Qd2; 27.Qd3 Qb6 28.Qc4 Rxf3 is simple and good for Black

27…Re8

Maintaining Black’s advantages and renewing the threat of …Qa6.

27…Bf6 28.Rf7 is surprisingly awkward 28…Qb5 (28…Qa6 29.Qxc5) 29.Nc3 (29.a4 Qxe2 30.Qxe2 Rxe2 31.Rxf6 is also pleasant for White but the text is much stronger) 29…Rf1+ 30.Rxf1 Qxf1+ 31.Qd1

a1) 28.Qc4 b5

a2) 28.Qd3 Qb6

Simply threatening …Qxe6

29.Rxh6 c4

a21) 30.Rxe7 Rf1+ An important in-between move (30…cxd3 31.Rxe8+ Kc7 32.Rh7+ Kd6 (32…Kc6 33.Rc8+ (33.e7 Rf1+ 34.Nc1 Rxc1+ 35.Kxc1 Qc5+ mates) 33…Kb5 34.e7 wins for White: the rook on c8 covers all Black’s counterplay!) 33.Rd7+ Ke5 34.Rd5+ Kf6 35.Rf5+ Kg7 36.Rf7+ is a draw as long as Black doesn’t stray onto g6 or h5!) 31.Nc1 cxd3 32.Rxe8+ Kc7 33.Rh7+ Kd6 34.Rd7+ Ke5 35.Rd5+ Kf4 The difference.

a22) 30.Qxd4 Rxe2 31.Qxb6 axb6 32.Rhh7 Rd8 33.Kc1 (33.a3 Rd1+ 34.Ka2 c3) 33…c3

a23) 30.Qxc4 Ba3

(30…Rc8 31.Qxc8+ Kxc8 32.Rh8+ (32.Rxe7 Rf1+ 33.Nc1 Rxc1+ 34.Kxc1 Qc5+) 32…Kc7 (32…Bd8 33.e7) 33.Rxe7+ is too murky for comfort!) 31.b3 (31.Qb3 Rf1+ 32.Kc2 (32.Nc1 Rc8) 32…Rc8+ 33.Nc3 d3+ 34.Kxd3 Rxf3+ which I thought must be winning. Komodo gives White -250!) 31…d3 32.Qxd3 (32.Rhh7 Rf1+) 32…Rf1+ 33.Kc2 Rc8+ 34.Kd2 Bb4+ mates very soon

a3) 28.Rc1 a6

looks like the safest, getting rid of any back-rank tricks and threatening …Qb5 (as the queen is now defended!) (28…Qa6 29.Rxe7; 28…Qb5 29.Nxd4; 28…Qb6 29.Qa4 is annoying)

29.f4 Qb5 30.Nxd4 Rxc2 31.Nxb5 Rxc1+ 32.Kxc1 axb5 33.e5

will require some analysis, but if anyone is better then it’s Black.;

b) 26.Rhg1 Rf2 27.Qd3 (27.Rg7 Re8) 27…Qb6 28.f4 Qxe6 29.Nxd4 Komodo! 29…Qd6 (29…cxd4 30.Qxd4) 30.Nf5 Qxd3+ 31.Rxd3 Bf6 is better for Black;

c) 26.Qc4 Recommended by Soloviov with the terse comment “intending Nf4”. I thought it was just plain bad!

c1) 26…b5

26…Rd8 27.f4 b5 transposes

27.Qd3 Rd8 I thought Black was virtually winning here. I’d got it completely wrong! (27…Bf6 28.f4 c4 29.Qf3 d3 30.Qxg2 Bxb2 31.Kxb2 Qb4+ 32.Ka1; 27…Rhg8 28.Nf4)

28.f4 c4 29.Qf3 wins!;

c2) 26…Rhg8 27.Nf4 (27.f4 b5 28.Qd3 c4 29.Nxd4 (29.Qxd4 Rxe2 30.Qe5+ Kc8) 29…Rxb2+ (29…cxd3 30.Nc6+) 30.Kxb2 Rg2+ 31.Qc2 Rxc2+ 32.Nxc2 Ba3+ 33.Nxa3 Qb4+ 34.Kc2 Qxa3 leads to perpetual) 27…b5 28.Qd3 followed by Nd5 28…Rf2 29.Rhf1 Rh2 30.Rfe1 intending Re2 blocking the second rank followed by a future Nd5: Komodo really likes White;

c3) 26…Qb6 27.Rhg1 (27.Rd3 was my first thought 27…Rxe2 (27…h5 was Komodo’s recommendation 28.Rb3 Qd6 Komodo was not impressed with my rook on b3) 28.Rb3 Qc6 29.Qxe2 c4 30.Rc1 Rc8 31.f4 d3 32.Qg2 (32.Qf3 d2 33.Rc2 cxb3 34.Rxc6 Rxc6) 32…Qxe6 (32…d2 33.Qxd2 Qxe4+ 34.Ka1 cxb3 35.Rxc8+ Kxc8 36.Qd7+ Kb8 37.Qe8+) 33.Rbc3 b5 is an initiative for Black) 27…Rf2 28.Rgf1 Rg2 29.Rg1 is equal according to Komodo;

c4) 26…Rf8

Another idea of mine, stopping Nf4 and looking to ruin White’s pawn structure after …Rxf3. White has to tread very carefully:

27.Rxh6

27.f4 Qa6 A Komodo touch! (27…b5 28.Qd3 c4 29.Qf3 was another disaster for my …b5 & …c4 idea) 28.Qxa6 bxa6 is difficult for White

27…b5

27…Rxf3 28.Rh8+ Kc7 (28…Rf8 29.Rxf8+ Bxf8 30.Nf4 feels uncomfortable) 29.Rh7

28.Qd3 c4

29.Qxd4 The only move to hold the position.

29.Nxd4 Qa4 (29…cxd3 30.Nc6+ Kc7 31.Nxa5 Rxf3 32.Rh7 Rff2 33.Rxe7+ Kb6 34.Rb7+ Ka6 35.Nc4 Kxb7 36.e7 bxc4 37.e8Q Rxb2+ 38.Ka1 Rxa2+ 39.Kb1 was my drawing line) 30.Nc6+ Ka8 missed that one! 31.Qd4 Bc5 32.e7

32…Rc8 wins

29…Rxe2 30.Qe5+ Kc8

30…Qc7 31.Qxc7+ Kxc7 32.Rh7 Rxf3 33.Rxe7+ Kb6 leads to equality

31.Qd5 Kb8 32.Qe5+

is a draw by repetition

Some complicated variations there, but the general conclusion is clear: White needs to be a little careful after 23.Ne2.

26.Nf4 Qd6 27.Qh2

A confusing position: Black finds it very hard to put the knight on f4 under any extra pressure without setting himself up for f4–f5 with tempo!

27.e5 Qxe5 28.Ng6 Qxe6 29.Nxh8 Rxh8 looks pretty OK for Black

27…Re8

27…Rf8 28.Ng6

27…Bg5 28.Nd5 Qxh2 29.Rxh2 with f4 to follow 29…Rf8 30.Rf1

28.Ng6

It feels very thematic to make such good use of the square White has undermined from the early opening stages!

28…Qxh2 29.Rxh2 Rhg8 30.Ne5

A sharp attempt to get more out of the position than a better but complex double-rook ending

30.Nxe7 Rxe7 31.Rxh6 Rf8 32.Rf1 Rf4 33.Kc2 Kc7 34.Kd3 is given by Soloviov as an advantage for White 34…Kd6 35.b4 cxb4 36.Kxd4 Rxe6 37.Rhh1 followed by Ke3 looks much easier for White to play.

30…Bd6

30…Kc8 with the idea of 31.Rxh6 Bg5 is Soloviov’s (better) recommendation. The game continuation leads to disaster

31.Nd7+ Kc7 32.Rxh6 Rh8 33.Rg6 Reg8 34.Rxg8 Rxg8 35.e5 Be7 36.f4

1–0

So where did Black really go wrong? After 21…Kb8 22.e4 d4, 23.Rxd4 (instead of Bogoljubov’s 23.Ne2) would have given White an appreciable advantage.

21…Qc5

is recommended by Soloviov and is indeed a more stubborn continuation. Black counters the threat of Nxd5 by blocking the c-file and prepares to meet White’s final and most important light-square lever e4 with …d4.

22.e4

22.Rh5 was Komodo’s favourite for a long time but after 22…Bg5, I didn’t feel that the inclusion of these moves was really helping White.

22…d4 23.Ne2 Rf8 24.Rhf1

24.Rdf1 is an interesting alternative

24…Qxc2+ 25.Kxc2 c5 26.b4

Komodo’s refinement: 26.f4 gxf3 27.gxf3 Rf6 28.f4 Rxe6 29.Kd3 Ra6 30.a3 Rb6 gives Black extra play on the queenside in comparison to 26.b4. See the article “Lessons from Haarlem 2016 – the missing …h6” for a detailed discussion of this type of rook manoeuvre designed to elicit weaknesses from the opponent’s pawn structure.

26…b6

Now the Black rook no longer has access to the queenside. Both Komodo and Stockfish think that Black’s best chances arise after 26…Rf6 27.bxc5 Rxe6 28.Rxd4 though after a sample line 28…Bxc5 29.Rd5 b6 30.Kd3, Black still needs to be a little careful that White doesn’t mobilise his e- and f-pawns.

27.f4 gxf3 28.gxf3 Rf6 29.Kd3 Rhf8 30.f4

looking for f5 and Nf4 is good for White despite the pawn deficit. White’s plan is simply to roll the e- and f-pawns forward accompanied by the White king. Note how White’s mining of Black’s light-square occupation has left White’s e and f-pawns free of opposition. Note also how useless the Black dark-squared bishop is in getting his own queenside majority going! White’s plan of exchanging his way to a knight vs dark-squared bishop position has paid off: all the bishop can do is to wait until it gets attacked by the onrushing e- and f-pawns.

After 18…fxe6 19.Qxe6 (You might mean 19.Qxg6) – both between diagrams and below diagram

Hi Carsten, thanks! Corrected! Best Wishes, Matthew