Invigorated by preparing a training on endings for some keen youngsters, I’d like to share some general thoughts about activity in endings, and in particular in rook and pawn endings.

Why are endgames important to study? Mastering endgames means understanding how to maximize the mobility and activity of each of your pieces, and understanding how to marshal and combine their strengths. In a middlegame, the weight of material at your disposal is often enough to mask the inefficient deployment of a certain piece: there is always a queen or another minor piece available to create compensating threats. In an endgame, with so little material on the board, an ineffective piece is often tantamount to defeat. Logically therefore, a part of endgame mastery also means understanding how to limit the activity of the opponent’s pieces.

In this blog article, we will focus on rook and pawn endings which occur most often in practical play. We’ll start off with a few trivial examples. Playable versions of the games in this article are available at http://cloudserver.chessbase.com/MTIyMTYx/replay.html An accompanying video is to be found at https://youtu.be/mbhZC0RpoVc

K&R vs K

Delivering mate in the K&R vs K ending involves maximizing the activity of your own king and restricting the opponent’s king to the maximum degree.

K&P vs K

This K&P vs K ending can only be won if the white king’s activity is maximized and used to push the black king away from the queening square of the white pawn.

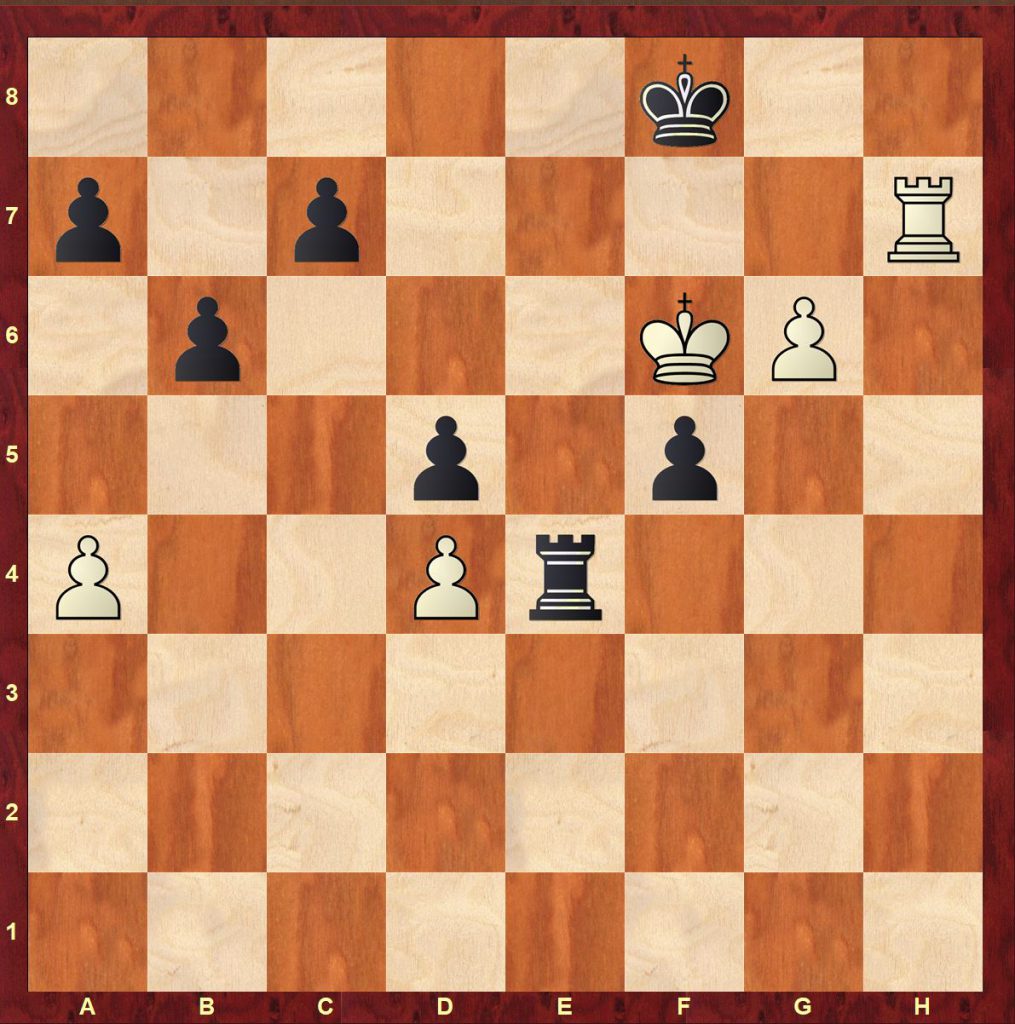

Lucena position

The slightly less trivial Lucena position is an excellent example of optimizing the activity of each individual piece and then combining their activity together.

The White king has done a sterling job in pushing away the black king from White’s passed pawn; however, the black rook and king are not giving up without a fight! Both pieces are combining to hem in the white king and prevent it from moving away and letting the pawn queen. White’s first move is very natural to chase away the black king and decrease its influence while increasing the mobility of his own king.

1.Rf1+ Kg7

Now however, things get more complicated. The White king is now free to roam, but White’s ambition to queen the pawn is thwarted by Black’s typical idea of perpetual rook checks from distance.

As has often been said, the best way to optimize your position is to talk to your pieces. I’m sure the white king would tell us that he’s really doing his best, but the white rook might look a little embarrassed and squirm awkwardly if we challenged him! Rooks can move an unlimited number of squares forwards and sideways which means that they realize their full potential when they exert influence both along files and ranks. This is particularly true in endgames due to the reduced material: there is simply a lot more room for rooks to manoeuvre! In this position, the rook is performing a sterling job along the f-file but as yet it is not usefully employed along the (first) rank. White’s next move changes all that.

2.Rf4 Rc1 3.Ke7 Re1+ 4.Kd6 Rd1+ 5.Ke6 Re1+ 6.Kd5 Rd1+ 7.Rd4

White’s rook gains the possibility to combine with the white king along the 4th rank while still keeping the Black king at bay along the f-file. Perfect activity with just 3 white pieces on the board!

Grant-Arkell Largs 1997

The following game which Natasha and I quoted in “Chess for Life” is another nice illustration of the effect of maximizing the activity of your rook along rank and file.

The black rook on a4 is already well-placed, tying down the white rook to the defence of the a2-pawn while preventing the white king from activating itself any further than the third rank. However, you can always do more!

36…Ra3 37.Kd2

Now that Black has restricted the white pieces to the maximum degree, it’s time to think about a winning scheme. Black has a pawn majority on the kingside so that is where he should look to create a passed pawn. Keith’s approach is very nice: he swaps his h-pawn for White’s g-pawn and in this way creates a protected passed pawn on the f-file behind which his king can advance. It’s a nice illustration of the helplessness of the opponent in the endgame when the activity of his pieces has been so severely curtailed. White has no reply to the methodical expansion of Black’s pieces.

37…h5 38.Kc1 h4 39.Rf2 h3

40.Kb2 hxg2 41.Rxg2 Rh3 42.Kc2 Re3 43.Kd2 Ra3 44.Ke1 f5 45.Rc2 Kh6 46.Kf2 Kh5 47.Kg2 g5 48.Rf2 f4 49.Rc2 Kh4 50.Rb2 g4 51.Rc2 f3+ 52.Kg1 Rd3 53.a4 Ra3 54.Rc4 Ra1+ 55.Kf2 Ra2+ 56.Ke3 Re2+ 57.Kd3 Rxh2 58.Rc7 Ra2 59.Rxa7 f2 60.Rf7 Kg3 0–1

Capablanca-Tartakower New York 1924

A famous example of a difference in king activity in rook and pawn endgames is the game played by Capablanca against Tartakower, a game which I first saw as a young child in – I believe – Irving Chernev’s “60 Most Instructive Games Ever Played”

Black’s king is pinned to the back rank and White’s rook is lording it over the 7th rank, but Black’s rook is threatening to cause some damage by capturing the loose pawn on c3 and driving White’s king backwards. Capablanca’s solution is radical: anything for the activation of his king! It’s only by combining his king and rook (just as in K&R vs K) that the opposing king can be put in danger.

35.Kg3 Rxc3+ 36.Kh4 Rf3 37.g6

[The most elegant and efficient, activating White’s passed pawn and freeing a path for the White king to f6]

37…Rxf4+ 38.Kg5 Re4 39.Kf6

[The last important point: White leaves the black pawn on f5 as a barrier to Black perpetual checks from the back. The king is invulnerable to interference on f6 and that makes it a fearsome piece indeed!]

39…Kg8 40.Rg7+ Kh8 41.Rxc7 Re8 42.Kxf5 Re4 43.Kf6 Rf4+ 44.Ke5 Rg4 45.g7+ Kg8 46.Rxa7 Rg1 47.Kxd5 Rc1 48.Kd6 Rc2 49.d5 Rc1 50.Rc7 Ra1 51.Kc6 Rxa4 52.d6 1–0

Philidor’s Position

A passive king is however not necessarily the end of the game for the defender if he is also able to place a limit on the activity of the opponent’s king. This is the essence of Philidor’s famous position:

The black king is pinned to the back rank, but the game is not over unless White manages to maximize the activity of his own king and combine this with the activity of his rook. The move 1…Ra6 prevents this, while after 2.e6, Black manages to draw with the standard perpetual rook checks from distance:

Note that if it was White to move in the position, he could make a decent winning attempt by playing 1.Kf6 after which Black’s attempt to maximize the activity of his rook by allowing it to check the white king either from the back rank or along the sixth rank is thwarted. 1…Ra6+ is met by 2.e6 while 1…Rf1+ is met by 2.Ke6 when the king hides in front of its passed pawn.

Arkell-Wu Li Coventry 2004

This imperative to prevent the opponent from maximizing the activity of all of his pieces is a good explanation of the typical rook ending technique of sacrificing a pawn to activate the rook. Take a look at this ending, also quoted in “Chess for Life” from the game Arkell-Wu Li

54…Kf7 55.Kh6 Kg8 56.Re1 1–0

The game’s continuation did nothing to curtail the tremendous difference in activity between the white and black kings. However, Black’s best continuation 54…Rd2 55.Rxc7 Rh2+

would have given Black the opportunity of driving the white king back from its dominant position via the normal perpetual checks from distance. The resulting position still looks scary for Black, but it is drawn.

Alekhine-Capablanca

Perhaps one of the oddest things about chess endings – which I only realized consciously while watching Sergei Tiviakov’s DVD for Chessbase on converting advantages – is the common use of zugzwang as a means – often the only one – of winning a won position. It’s quite weird if you think about it: you spend masses of time engineering all of your pieces onto their ideal squares and then at the moment supreme… you just wait for the opponent to fall over! The famous final game of the 1927 World Championship match between Alekhine and Capablanca is a classic example of this:

Here Alekhine chose the less accurate 67.f4 but as Alekhine pointed out after the game, the most thematic was:

67.Kg7 Rf3 68.Kg8 Rf6 69.Kf8 Rf3 70.Kg7 Rf5 71.f4

71…Kb7 72.a6+ Ka7 73.Ra3 Kb8 74.a7+ Ka8 75.Ra4 and White simply has to wait for 1–0

I found it really useful for myself to refresh my general thoughts about activity in endings and explain them to other people: I hope it was useful for you too!

I think many introductory books give the impression that Zugzwang occurs primarily in pawn endings. One case that has made it into texts is queen f5, king h6 against king g8, rook g7. I think there was a Zugzwang finish to a Bronstein-Reshevsky game at the 1953 Candidates’ tournament.

My mistake! It’s queen h5 and king f6 against king g8, rook g7. The king needs to be close to the center.

I really would like to see that the misnaming “Lucena position” for the “Salvio barrier” (my naming) could be stopped! And also the bad wording by Nimzowitsch who called it “Brückenbau” (building the bridge) — what a derelict bridge this would be … The original source is: Salvio. Il Puttino, altramente detto, il Cavaliero Errante, del Salvio, sopra el gioco de Scacchi, Neapel 1634, p. 69.

The actual position is with a pawn on b7. 1K1k4/1P6/8/8/8/8/r7/2R5 w – – 0 1 “Del Signor Scipione Genouino mio maestro.” 1. Rc4 . Salvio: “in questo gioco auuerta il n. no pertere mai la filera del detto Rocco, perche perderebbe subito il gioco […] n. gioca che vole” Rook on the a-file somewhere, for logical reasons on a3 or a1. 1. … — 2. Rd4+. King somewhere, Salvio: “el n. bisogna andare all’ altra filera” 2. … Ke7 3. Kc7 Rc2+ 4. Kb6 Rb2+ 5. Ka6 Ra2+ 6. Kb5 Rb2+ 7. Rb4. Salvio: “il B. coprendosi con il Rocco vince per forza.” 1-0 Best regards, Ulrich

Pleased to join.