Although I love analysing attacks and crunching out reams of variations, it’s often just as useful to reflect quietly on the general course that a game has taken. The aim then is not to discover the whole truth about the position, but rather to get into the heads of the players and to understand the reasons that motivated their decisions. I was sitting in the train looking through the game Bogolyubov-Alekhine 25th game of the 1934 World Championship Match the other day, and my first impression was that both Bogolyubov and Alekhine had made a number of poor decisions. It’s only when I closed my eyes, tried to picture myself in their shoes and thought “what would I do here?” that I started to understand some of the subtle pressures and difficulties in the position. In this article, I wanted to give you an idea of how this process works, and at the same time to introduce you to an Alekhine theme in the opening: …dxc4 and …Bg4

Bogoljubov – Alekhine

World Championship 1934

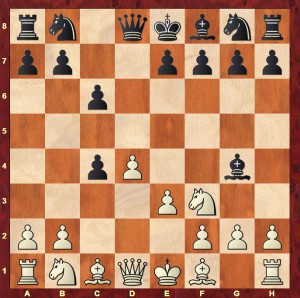

1.d4 d5 2.Nf3 c6 3.c4 dxc4 4.e3 Bg4

The combination of taking on c4 followed by playing the bishop to g4 was a favourite theme of Alekhine’s in Queen’s Pawn openings. In his Best Games Collection, he quotes a number of games with this idea in the Queen’s Gambit Accepted – which he also played against Bogolyubov in this match, achieving an easy draw.

1.d4 d5 2.c4 dxc4 3.Nf3 a6 4.e3 Bg4 5.Bxc4 e6 6.h3 Bh5 7.Nc3 Nf6 8.0–0 Nc6 9.a3 Bd6 10.Be2 0–0 11.Nd2 Bxe2 12.Qxe2 e5 13.dxe5 Bxe5 14.Rb1 Re8 15.Nf3 Qe7 16.Nxe5 Qxe5 17.Qc2 Rad8 18.Bd2 Qe6 19.Rfd1 Qc4 20.Bc1 Ne5 21.e4 h6 22.Be3 Rd3 23.Rxd3 Qxd3 24.Qa4 Qc4 25.Qc2 Qd3 26.Qa4 Qc4 27.Qc2 Qd3 ½–½ Bogoljubov -Alekhine Germany 1934

Funnily enough, while reading the book “A Chess Opening Repertoire for Blitz and Rapid” by Sveshnikov father and son, I saw that they recommended the opening variation 1.d4 d5 2.c4 dxc4 3. Nf3 c6 4.a4 Bg4! which is very similar to Alekhine’s idea!

5.Bxc4 e6 6.Nc3 Nd7 7.h3 Bh5 8.a3 Ngf6 9.e4 Be7 10.0–0 0–0 11.Bf4 a5 12.Ba2 Qb6 13.g4 Bg6 14.Qe2 Qa6 15.Qe3 b5

In principle, Black has played the opening very passively, conceding a double-pawn centre and easy development to White. However, in this position, Black is for choice. The threat of …b5–b4 in combination with Black’s piece pressure on e4 (via the Nf6 and Bg6) is extremely irritating for White. How and why have things gone wrong for White?

White’s discomfiture stems from his placement of the light-squared bishop on a2: it would be so much better on d3 reinforcing the e4 pawn! White was probably a little afraid of the …c5 break and wanted to support the advance of the d-pawn to d5 with a bishop on the a2–g8 diagonal. However, in general, White is well-developed and shouldn’t have anything to fear from the opening of the centre. In a similar position against Tony Miles, I came up with a development scheme of placing the rooks on c1 and d1 and the bishop on b1 and this would have been a pretty good idea here too.

1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 c6 3.Nc3 d5 4.Nf3 dxc4 5.a4 Bf5 6.e3 e6 7.Bxc4 Bb4 8.0–0 Nbd7 9.Qe2 Bg6 10.e4 0–0 11.Bd3 h6 12.Bf4 Rc8 13.Rfd1 Re8 14.h3 a6

15.Rac1 Qb6 16.Bb1

16…Bh7 17.Nd2 Qd8 18.Nc4 Nb6 19.Na2 Bf8 20.b3 Ra8 21.Kh1 Nc8 22.a5 Nd7 23.Nc3 Bb4 24.Na4 Qe7 25.Qg4 Nf6 26.Qf3 Na7 27.Bg3 Nd7 28.d5 exd5 29.exd5 Bxb1 30.Rxb1 cxd5 31.Ncb6 Nxb6 32.Nxb6 Rad8 33.Nxd5 Qf8 34.Nc7 Re7 35.Rxd8 Qxd8 36.Nd5 Re1+ 37.Rxe1 Bxe1 38.b4 Qe8 39.Nc7 Qc6 40.Qe3 Bxb4 41.Qxa7 Bxa5 42.Qb8+ Kh7 43.Ne8 b5 44.Nd6 f6 45.Qa7 Bb4 46.Nf5 Bf8 47.Qf7 Qc8 48.Nd4 Ba3 49.Ne6 Qg8 50.Qd7 Kh8 51.Bc7 Bb4 52.f4 Bc3 53.f5 b4 54.Bd6 1–0 Sadler – Miles Torquay 1998

However, these comments in no way detract from the cleverness of Alekhine’s play. The manoeuvre …a5 followed by …Qb6 (attacking d4 on the way)-a6 is a lovely of getting his queen developed with gain of tempo (due to the threatened exchange of queens) and it also shows excellent vision to spot the power of …b5–b4 instead of the standard break with …c5.

Strangely enough, these 2 players had already contested a game with a very similar course in the 23rd game of the match. In that game Bogolyubow had beaten Alekhine decisively:

Bogoljubow,Efim – Alekhine,Alexander [D23]

World Championship 1934, 23rd match game

1.d4 d5 2.Nf3 Nf6 3.c4 dxc4 4.Qa4+ c6 5.Qxc4 Bf5 6.Nc3 e6 7.g3 Nbd7 8.Bg2 Bc2 9.e3 Be7 10.0–0 0–0 11.a3 a5 12.Qe2 Bg6 13.e4 Qb6 14.h3 Qa6 15.Qe3

Amazingly similar isn’t it? In comparison with the main game however, White’s support of e4 is much stronger due to the bishop on g2 which both discourages and nullifies Black’s plan of …b5-b4.

15…c5 16.e5 Nd5 17.Nxd5 exd5 18.Bd2 Be4 19.Bc3 c4 20.Ne1 Bxg2 21.Nxg2 b5 22.f4 Qh6 23.Qf3 b4 24.Bd2 Nb6 25.g4 Qc6 26.f5 f6 27.Nf4 Rfc8 28.exf6 Bxf6 29.Ne6 c3 30.bxc3 Nc4 31.Bf4 Nxa3 32.g5 Bd8 33.Be5 Ra7 34.Qh5 Nc4 35.cxb4 Nxe5 36.dxe5 Bb6+ 37.Kh1 d4+ 38.Qf3 Qxf3+ 39.Rxf3 Rc3 40.Rff1 d3 41.f6 Rc6 42.Nxg7 Rxg7 43.fxg7 axb4 44.Rf6 Bd4 45.Ra8+ Kxg7 46.Rxc6 d2 47.Rc7+ Kg6 48.Rg8+ Kf5 49.Rf8+ Ke4 50.Rf1 Bxe5 51.Rc4+ Kd3 52.Rxb4 Bg3 53.Kg2 Be1 54.Rb1 Bh4 55.Rb3+ Ke2 56.Rb5 Ke3 57.Rd5 Ke2 58.Rf7

1–0

Back to the 25th game now!

16.Ne5

I would have been tempted to play 16.Bb1!

16…Nxe5 17.Bxe5 b4 18.Bxf6 Bxf6 19.Ne2

19…bxa3 20.bxa3 c5

21.Rac1 cxd4 22.Nxd4

22…Bxd4 23.Qxd4 Rfd8

The sequence of moves between move 16 and 23 contains a number of subtle little points. I’m going to examine each individually and then bring them together in an overall evaluation of the position.

A. White’s inconsistent play

White’s play makes a strange impression – a mixture of aggression and meekness.

AGGRESSION:

1.Occupying the centre with pawns on d4 and e4

2. Bishop on the a2–g8 diagonal, pointing at the Black king on g8

3. Expansion on the kingside with g4

4. Qe3 avoiding the exchange of queens

MEEKNESS:

Bogolyubov’s solution to Black’s pressure against e4 was rather limp

1. 16.Ne5 swapping off pieces

2. 18.Bxf6 giving Black the 2 bishops

When I see such a mix of styles from an opponent in one game, I always expect the advantage to come my way. For example, a meek move like 18.Bxf6 is not to my taste – I don’t like giving up the 2 bishops so easily – but it isn’t a disaster in itself. However, preface it with the aggressive 16.g4 – which weakens the kingside dark-squares (particularly f4) enormously – and it suddenly feels like a positional disaster.

B. 19…bxa3

This is a first raise-your-eyebrows moment for me. As I’ve explained, when I see a move like 18.Bxf6 on the board after an earlier 16.g4, then I’m looking for a Black advantage. In general, the side on top has the luxury of leaving options open for longer. Here I would want to maintain the cramping influence of the pawn on b4 (for example, it takes c3 away from the White knight) and leave the pawn on b2 as a target for the bishop on f6 and play 19…c5 immediately.

C. 22…Bxd4

A second raise-your-eyebrows moment for me. Black relinquishes the most obvious advantage in his position – the 2 bishops – and leaves himself with a bishop on g6 restricted by White’s kingside pawns (f3 will follow to reinforce the pawn on e4). What on earth is Black doing?

Let’s just step back for a moment and think generally. You have 2 ways to play advantageous positions.

1. You can invite a crisis, trusting that in the resulting complications, the side with the advantage will emerge victorious

2. Alternatively, you can try to convert your advantage into a position in which you enjoy a stable advantage. This last approach is always tricky to judge: if you get it wrong, you can end up flattening out your advantage to an insignificant edge.

Alekhine’s chooses very clearly for the second approach in this game. From move 19, he directs the play to the position reached after move 23. How do we assess the resulting position? And therefore how do we assess Alekhine’s decision?

First of all, who has the stronger minor piece – White or Black? White is keeping Black’s bishop on g6 out of play with his wall of kingside pawns (f3 will follow quickly to protect e4). However, White’s own bishop on a2 is also largely ineffective (it does prevent the redeployment of Black’s bishop with …f6 and …Bf7 by exerting pressure on e6, but this is of marginal value). Bizarrely enough, in many variations in the game, the bishop ends up being captured on a2! That’s because White’s bishop has difficulties finding any stable outpost whereas Black’s bishop is solidly supported on g6. White would ideally like to transfer the bishop to b5 and support it with a pawn on a4. However, this requires a great deal of cooperation from Black and Alekhine mentions the possibility of …a4 to prevent this setup.

Secondly, who has the safer king? This is the crux of the position. Black’s king is protected by a normal pawn structure, whereas White has played g4 (and will soon follow up with f3 to hold the e4 pawn). This gives Black a lovely complex of kingside dark-squares (e5,f4,g3) from which he can use his queen to target the White kingside.

Finally, who has the most weaknesses? That has to be White. Apart from the kingside dark-squares already mentioned, there is also the weak pawn on a3 which can easily be attacked by a Black queen on the f8–a3 diagonal or a Black rook on White’s 3rd rank.

When you add up these factors, you start to realise that Black has fairly good chances for a solid, riskless advantage. I was particularly intrigued how Stockfish would assess the position. He went for –0.67 which is almost a clear advantage for Black.

Alekhine is pretty laconic about this period of play. He doesn’t comment on 19…bxa3 and after 22…Bxd4 he just says “The exchange of the active f6 bishop at first sight looks surprising but in reality offers the greatest possibilities of exploiting the weak spots of White’s position both in the centre and on the kingside”]

24.Qc4 Qb7

24…Qd6 is another natural move, aiming for a nice soft spot on f4 for the Black queen while attacking the weak a3 pawn on the way.

25.f3 h5 26.Qe2 Rd4 27.Qe3 Rd7

28.gxh5

A weird decision, but understandable in a way. White reasons that with the pawns on f3 and e4, he still has a wall of pawns against Black’s light-squared bishop. Secondly, by exchanging off the h5 pawn, he stops Black from playing …h4 which creates a protected entry square for the Black queen on g3. However, the tempo he gains with the action (Rc5) is rather insignificant, while thanks to the availability of h5 for Black’s light-squared bishop, White’s kingside pawn structure is more vulnerable to attack.

28…Bxh5 29.Rc5 Bg6 30.Rfc1 Rad8 31.Bc4 Rd1+ 32.Bf1 Rxc1 33.Rxc1 a4 34.Rc4 Rd1 35.Rb4

35.Rxa4 Rxf1+

35…Qc7

The play in the last 10 moves has not been perfect from either side, but you see that White has a fairly thankless task defending this position. With threats all over the shop, Bogolyubov feels compelled to advance his f-pawn, but this is a defensive disaster: the bishop on g6 is now a strong piece again, tying down a White piece to the defence of the e-pawn.

36.f4 Qd8 37.Qf2 f5 38.e5 Be8

The bishop is even stronger now! It’s heading for the a8–h1 diagonal.

39.Rb6 Qc8 40.Rd6 Rc1 41.Qd4 Kh7 42.Kf2 Qc2+ 43.Qd2 Qc5+ 44.Qe3 Rxf1+

0–1

Very nice explanations again – thanks, Matthew! I wonder what you think of Bogo’s play more generally. His reputation probably suffers from the fact that the two main modern sources (as far as I know), Charashin’s CD and Soloviov’s book, are quite scarce. Anyway, Kasparov is very dismissive – he calls Bogo a ‘convenient’ opponent for Alekhine and implies that he was really only strong enough to allow Alekhine to show off his risky play. Do you think that’s fair? James

Hey James, thanks for that! I’ve been studying Bogolyubow’s play quite a bit recently as I’m writing some blog articles on the 1929 World Championship Match. Very mixed feelings! He had a really impressive tournament record in the 20’s so if Capablanca wasn’t going to get a rematch, he deserved to be next in line. The main problem is that his play wasn’t particularly attractive – I played through about 200 of his wins quickly, and there weren’t many moments where you stop and think “Wow!” as you do with Alekhine or Capablanca. On the other hand, a few of his wins against Alekhine from the 1929 Match were pretty powerful. I’ve ordered the Soloviov book so I’m looking forward to that! In general though, I think that Kasparov’s comments are rather unfair, in the same way that Euwe is often unfairly seen as one of the weaker World Champions! Best Wishes, Matthew