Bogolyubow’s preparation for the World Championship match was to take part in the strong Carlsbad event of 1929 in which he came 8th with 11,5 / 21 (Nimzowitsch won with 15/21). He lost a superior ending (2R & 2Bs vs 2Rs & 2Ns) with Black in the last game against Becker in the 21st round and had to face Alekhine with the same colour just 8 days later. Between 31st July and 19th September 1929, Bogolyubow played 29 top-level games in 50 days. I can imagine that he was looking forward to the 2-week break in the match after the 8th game!

It wasn’t a restful way to prepare for a tough World Championship but maybe Bogolyubow felt that he needed some top-level practice going into the match as his last tournament dated back to September 1928. In any case, Bogolyubow kept his customary good humour after the result as Nimzowitsch relates in his book of the tournament:

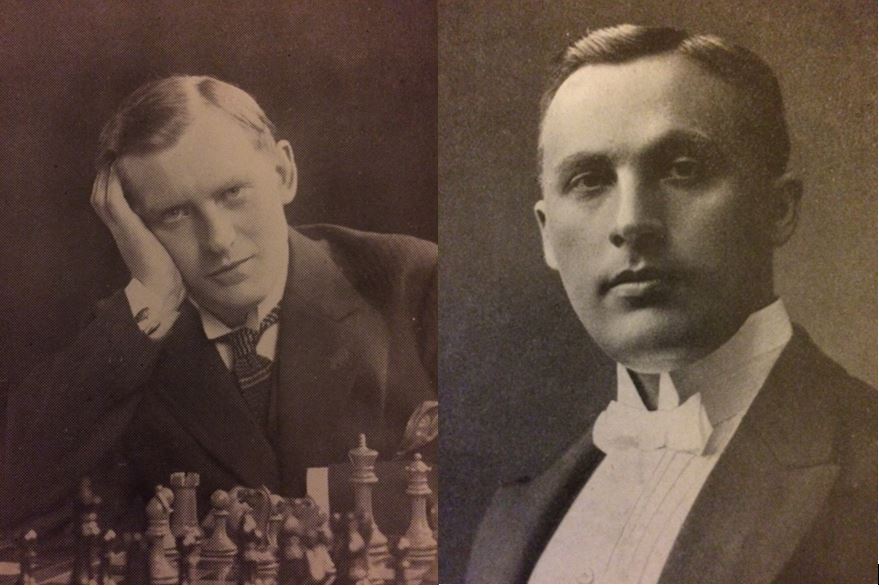

Alekhine hadn’t played that much serious chess either since his World Championship Match against Capablanca in 1927, concentrating mainly on a huge series of simultaneous exhibitions all over the world. The one exception was a modest event in Bradley Beach (3rd-12th June 1929) which he won with 8,5/9 (2nd L.Steiner 7/9, 3rd Kupchik & Turover 5,5/9) though his play was less convincing than the score suggests.

Alekhine described Bogolyubow’s approach in this fashion in his preview of the Carlsbad 1929 tournament written for the New York Times (cited from http://www.chesshistory.com/winter/extra/carlsbad.html)

Only eight days after the conclusion of the Carlsbad tourney I shall be called upon to defend my title. The challenger is no less a person than Bogolyubow, victor of the Moscow and Kissingen tourneys. Consideration for himself apparently did not prevent this grand master from entering the lists at Carlsbad, and in this connection the following must be taken into account: a challenger has much less to risk than the defender of the title.

Bogolyubow says he welcomes such active training before his match with me as this tourney imposes. It will soon be demonstrated who is right, Bogolyubow with his reckless optimism or I in my determination to husband my powers by practice and a rigid abstention on this occasion.

Assuming that Bogolyubow had already decided what he was going to play against Alekhine beforehand, it’s interesting to look at the openings that Bogolyubow chose at Carlsbad. It seems that he was keeping some of his preparation under wraps. With such a long tournament however, it was impossible not to give away some clues:

| Colour Bogolyubow | Opening | Choice Carlsbad | Choice match vs Alekhine | Conclusion |

| White | Nimzo-Indian – 1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Bb4 | 4.Nf3 (twice)

0/2 vs Nimzowitsch and Johner |

4.Qb3 (3 times) | Did not reveal his preparation for the match |

| White | Queen’s Gambit Declined – 1.d4 Nf6 2.Nf3 e6 3.c4 d5 | Many different choices:

i. Delayed development of the Nb1 after 4.Bg5 Nbd7 5.e3 (3 times against Matisons, Marshall and Menchik)

ii. 4.Nc3 Be7 5.Bf4 (once) against Maroczy

iii. Standard Bg5 lines against the Orthodox QGD (twice against Gilg and Thomas) |

Standard Bg5 lines leading to the Cambridge Spring (twice) via Slav move order (1.d4 d5 2.c4 c6 3.Nf3 Nf6 4.Nc3 e6 5.Bg5)

Exploited opponent’s Slav move order to transpose to the Meran after 4.e3 e6 5.Bd3 later in the match |

Not clear what Bogolyubow would play in the match but showed a lot of his possibilities. |

| White | Ruy Lopez – 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bb5 | Once against Vidmar | Twice against Alekhine in the latter stages of the match | Revealed a little preparation but Vidmar chose a different line with Black. |

| Black | Semi-Slav Meran – 1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 c6 3.Nf3 d5 4.e3 e6 | Once against Yates (5.Nc3 Nbd7) | Twice (23rd and 25th games where Alekhine played 5.Bd3) | Revealed his preparation. |

| Black | Slav – 1.d4 d5 2.c4 c6 3.Nc3 Nf6 | Once against Tartakower (who played the unusual and dubious 4.Bg5 which Bogolyubow met with 4…dc) | Bizarrely enough Alekhine also used 4.Bg5 in the 13th game but Bogolyubow varied with 4…e6

This Slav move order was also used continually in the match |

Revealed his preparation, though not the fact that it would be his most important weapon. |

| Black | King’s Indian – 1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 g6 3.g3 | Once: 3…Bg7 vs Capablanca | Once: 3…c6 | Revealed his use of the King’s Indian but varied when Alekhine repeated Capablanca’s line. |

| Black | Cambridge Springs – 1.d4 d5 2.Nf3 e6 3. c4 Nd74.Nc3 Ngf6 5.Bg5 c6 6.e3 Qa5 | Once vs Samisch (and another attempt vs Spielmann) | 4 times | Revealed his use of this variation. Alekhine followed the game against Samisch until move 11 when Bogolyubow varied (11…Bxc3+) Alekhine played Bogolyubow’s 11…Qc7 with Black in the next game! |

The course of the match – games 1-8

In this article, I would like to focus on the course of the first 8 games. This was probably the most interesting part of the whole match.

After a crushing win in the first game (discussed in a previous blog article http://matthewsadler.me.uk/chess-for-life/alekhines-themes-move-like-morphy/) Alekhine was frustrated in the next 2 games, failing to convert 2 winning endgames after strong disciplined play in the 2nd game, and old-fashioned “keeping on playing” determination in the 3rd game. All credit to Bogolyubow for keeping on fighting until the very end, but the draw in each case was primarily due to Alekhine’s lapses rather than to Bogolyubow’s good defence:

Bogoljubow,Efim – Alekhine,Alexander

World Championship 1929, 2nd Match Game

1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Bb4 4.Qb3 c5 5.dxc5 Nc6 6.Nf3 Bxc5 7.Bg5 h6 8.Bxf6 Qxf6 9.e3 b6 10.Be2 Bb7 11.Ne4 Qe7 12.0–0 0–0 13.Rad1 Rfd8 14.a3 Rac8 15.Qc2 d5 16.cxd5 exd5 17.Nxc5 bxc5 18.Rfe1 d4 19.Bd3 dxe3 20.Rxe3 Qf6 21.Rde1 Nd4 22.Nxd4 cxd4 23.R3e2 g6 24.Qd2 Ba6

A typically active offer from Alekhine which Bogolyubow unwisely accepts. To me, it’s curiously reminiscent of the 10th game where Bogolyubow also allowed Alekhine to push a passed pawn much further than he should have been able to!

Bogoljubow,Efim – Alekhine,Alexander

World Championship 1929, 10th Match Game

29…Qb4

Instead of trying at all costs to hold his blockade on c4 with 30.Rc1 (which should be possible without too much difficulty) Bogolyubow allows Alekhine to push his c-pawn all the way to c3.

30.Qc2 c4 31.Ne2 Bf6 32.g3 c3 33.Rb1 Qa5 34.Kg2 Rd8 35.Qe4 Rd2 36.Qc4 Rc2 37.Rd1 Qb6 38.Nd4 Qd8 39.Rd3 Bxd4 40.Rxd4 Qf6 41.Rf4 Qe5 42.e4 Rd2 43.Qc8+ Kh7 44.Rxf7 Qxe4+ 45.Kh3 Rd5 46.Rf4 Rh5+ 47.Kg4 Qe2+ 48.f3 Rg5+ 49.Kh3 Qf1+ 50.Kh4

0–1

Back to the main game now:

25.Bxa6 Qxa6 26.Qxh6 d3 27.Rd2 Re8 28.Red1 Rc2 29.h3 Qf6 30.Kh1 Rxb2 31.f3

31.Rxd3 Qxf2 32.Rg1 is a tiny bit unpleasant, but you can imagine that White should grab the opportunity to get rid of the enormous passed pawn on d3. After spurning this opportunity, White is in big trouble!

31…Rxd2 32.Qxd2 Qd4 33.Qb4 Qf2 34.Kh2 Re2 35.Qb8+ Kg7 36.Qg3 Qd4 37.Qg4 Qe3 38.Qg3 d2 39.f4 Qe4 40.f5

40…Kh6

An amazing error from Alekhine and completely uncharacteristic: he was fantastic in major piece endgames.

40…Qc2 is given as winning by Winter and Yates, and I cannot improve on their analysis! 41.fxg6 (41.f6+ Kh7 42.Qh4+ (42.Qb8 Qxd1 43.Qf8 Rxg2+ 44.Kxg2 Qe2+ 45.Kg3 Qe5+ wins) 42…Kg8 43.Qh6 Qc7+ 44.Kg1 Qc5+ 45.Kh2 Qe5+ wins) 41…f5 followed by taking the rook on d1: White doesn’t have any hopes of perpetual check.

I guess the answer for Alekhine’s mistake lies in this comment quoted in Sergei Soloviov’s “Bogolyubow The Fate of a Chess Player”

41.fxg6 fxg6 42.h4 Qd5 43.Qg4 Qe5+ 44.Qg3 Qd5 45.Qg4 Re4 46.Qg5+ Qxg5 47.hxg5+ Kxg5 48.Rxd2 Ra4 49.Rd3 Kf4 50.Rh3 g5 51.Rb3

½–½

Alekhine,Alexander – Bogoljubow,Efim

World Championship 1929, 3rd Match game

1.d4 d5 2.c4 c6 3.Nf3 Nf6 4.Nc3 dxc4 5.a4 Bf5 6.Ne5 e6 7.f3 c5 8.dxc5 Qxd1+ 9.Kxd1 Bxc5 10.e4 Bg6 11.Bxc4 Nc6 12.Nxc6 bxc6 13.Bf4 Nh5 14.Bd2 Rb8 15.Kc2 e5 16.Rhe1 Nf4 17.Bxf4 exf4 18.Rad1 Ke7 19.Ne2 Bf2 20.Nd4 Rbc8 21.Rf1 Bxd4 22.Rxd4 Rhd8 23.Rfd1 Rxd4 24.Rxd4 f6 25.Kc3 Be8 26.b3 Rc7 27.Bg8 h5 28.Kc4 h4 29.h3 Rd7 30.Rxd7+ Kxd7 31.Kc5 g5 32.Bc4 Kc7 33.Be6 Bh5 34.b4 Bg6 35.Bc4 Be8 36.Be6 Bg6 37.a5 Bh5 38.Bc4 Be8 39.Be6 Bh5 40.Bb3 Be8 41.Bc4 Bg6

Bogolyubow offered a draw at the adjournment but Alekhine elected to carry on.

42.b5 cxb5 43.Bxb5 Bf7 44.Bc4

A critical position according to Winter and Yates.

44…Bg6

A big mistake according to Winter and Yates.

44…Bxc4 45.Kxc4 Kc6 is drawn according to Komodo. I thought that White would keep a slight edge in the Q & P ending, but I’d missed something! 46.a6 Kd6 47.Kb5 Kd7 48.Kc5 Kc7 49.Kd5 Kd7 50.e5 fxe5 51.Kxe5 Kc6 52.Kf5 Kb6 53.Kxg5 Kxa6 54.Kxf4 Kb6 55.Kg5 Kc6 Black can afford to run back to cover the f-pawn due to the advantageous structure on the kingside. (55…a5 56.f4 a4 57.f5 a3 58.f6 a2 59.f7 a1Q 60.f8Q was my line with an advantage for White) 56.Kf4 (56.f4 Kd7 57.Kg6 Ke7 58.Kg7 Ke6 is a draw) 56…Kd5 57.Ke3 a5 58.Kd3 Ke5 59.Kc4 Kf4 60.Kb5 Kg3 61.Kxa5 Kxg2 As his h-pawn is so far advanced, Black can allow White’s pawn to run: he will queen his own pawn in time 62.f4 Kxh3 63.f5 Kg4 64.f6 h3 65.f7 h2 66.f8Q h1Q draws

44…Be8 45.Be6 Bc6 is best according to Winter and Yates, covering d5 and thus preventing the plan in the game 46.Bb3 (46.Bg4 Hoping to save a tempo by achieving e5 and Kd5 while already protecting the f3 and h3 46…Bb7 keeps the king out of d5 (46…Be8 47.Kd5 Bf7+ 48.Be6 Be8 49.e5) ) 46…Be8 (46…Bxe4 47.fxe4 g4 48.Bd1; 46…g4 47.hxg4 Bxe4 48.Bd5 Bd3 49.Bc4 Bg6 is ingenious but loses the f4 pawn in the long run after White organises Kd4, Bd3 and eventually Ke4) 47.Bc4 A subtle attempt to force the position in the game 47…Bc6 (47…Bg6 48.Be6 transposes to the game…) 48.Bb5 Bb7 49.a6 Bc8 50.Kd5 is the idea when Black’s pieces are awkward though it will most likely not be enough. However, it emerges that keeping the White king out of d5 is not so crucial as long Black is willing to do a little calculation.

45.Be6 Kd8

A really serious mistake. Now Black really is lost.

45…Be8 46.e5 fxe5 47.Kd5 wins according to Winter and Yates in their book on the 1929 World Championship Match. However, this just seems to lead to the (drawn) position that occurs later in the game 47…Bb5

48.Kxe5 Bf1 49.Kf6 Bxg2 50.Bg4 Kd6 51.Kxg5 Ke5 52.Kxh4 Kd4 53.Kg5 Ke3

46.Kd6 Ke8 47.e5 fxe5 48.Kxe5 Ke7 49.Bf5 Bf7 50.Bd3 Be6 51.Bg6 Bc4 52.Kf5 Bf1 53.Bh5

53.Kxg5 Bxg2 54.Kg4 wins!

Alekhine must have underestimated how quickly Black’s king could initiate counterplay against his pawns

53…Bxg2 54.Bg4 Kd6 55.Kxg5 Ke5 56.Kxh4 Kd4 57.Kg5 Ke3 58.h4 Bxf3 59.Bxf3 Kxf3 60.h5 Ke4 61.h6 f3 62.h7 f2 63.h8Q f1Q 64.Qa8+ Ke5 65.Qb8+ Ke6 66.Qxa7 Qf5+ 67.Kh4 Qf4+ 68.Kh3 Qf3+ 69.Kh2 Qe2+ 70.Kg3 Qe1+

A great escape for the challenger!

½–½

I have the feeling that the frustration Alekhine experienced at letting Bogolyubow off the hook in consecutive games played its part in the next 5 games which were all decisive. In game 2, Alekhine had not faced any particular problem with Black and he had outplayed his challenger without risk from a relatively simple position. The natural tactic would be to sit back and ask Bogolyubow to demonstrate something new in this line. However, it seems to me that Alekhine lost his equilibrium a little and in his next 2 Black games, he started to vary himself with somewhat experimental ideas. At this moment we see Bogolyubow’s strength emerging.

Just a little digression, Bogolyubow is a player I’ve always found difficult to appreciate. He seemed efficient at getting past the second-rank masters, good against his peers like Reti (career score: 19,5/29), Spielmann (career score: 26,5/44) and Tartakower (career score: 15/26) and – just like everyone else around that time – suffering against the very top guys like Capablanca (career score: 1/7), Lasker (career score: 2/8) and Alekhine (career score: 36/94). However, I couldn’t warm to his style which seemed to be mostly about playing decently, avoiding major blunders and then picking up the easy spoils when his opponents did (which happened a lot more regularly in those days).

However, looking at Bogolyubow’s play in the context of the match, I got a better idea of what he was capable of. When Alekhine started experimenting, Bogolyubow reacted very cleverly. He avoided overreacting which would allow Alekhine to demonstrate his wonderful feel for activating his pieces quickly at an early stage in the game (see http://matthewsadler.me.uk/chess-for-life/alekhines-themes-move-like-morphy/ as mentioned before for an example of that!) but at the same time he avoided excessive passivity which would lead to a similar result! He got his approach just right and in so doing, he set Alekhine opening problems to solve that were too difficult even for the World Champion. Take a look at game 4:

Bogoljubow,Efim – Alekhine,Alexander

World Championship 1929, 4th match game

1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Bb4 4.Qb3 c5 5.dxc5 Na6

A sharp and risky move that to my knowledge had been played just a couple of times earlier. Bogolyubow reacted in the most principled way.

6.a3 Bxc3+ 7.Qxc3 Nxc5 8.f3

An excellent choice by Bogolyubow. I imagine that Alekhine was looking forward to ideas such as 8.b4 Nce4 9.Qd3 d5 10.cxd5 Nxf2 as occurred in the game Thomas-Winter London 1927. Bogolyubow’s choice had been played by Rubinstein against Johner in the 15th round of the Carlsbad tournament just before the match so I’m sure both players were familiar with this way of playing.

8.f3 prevents any immediate central adventures by taking away e4 from the Black knights. It also threatens to gain central space with e4 and to clamp down on the dark square weaknesses (d6 in particular) that Black has left himself by combining the move 4…c5 with the exchange of the dark-squared bishops. I’m sure that Alekhine was trying continually during the game to get the explosive …d5 break working but the realisation was too difficult and he ended up accepting an inferior and passive position. It was only later in 1990 that Nick de Firmian showed a way of playing that I’m sure Alekhine would have loved to have thought of

8…a5

8…d5 9.cxd5 b6

10.b4 Na4 11.Qb3 b5 12.e4 a6 13.Ne2 0–0 14.Bg5 h6 15.Bh4 exd5 16.e5 Re8 17.f4 g5

18.Bf2 Ne4 19.Bd4 Be6 20.Qf3 Rc8 21.f5 Bd7 22.Ng3 Rxe5

23.Be2

23.Bxe5 Qe8

23…Qe8 24.Nh5 Rxf5 25.Qe3 Rc3 26.Bxc3 Naxc3 27.Bg4 d4 28.Qxd4 Nc5+ 29.Kd2 Nb3+ 30.Kxc3 Nxd4 31.Bxf5 Qe3+ 32.Bd3 Bf5 33.Rad1 Ne2+ 34.Kc2 Qe5 35.Kd2 Qb2+ 36.Ke3 Bg4 37.Rd2 Qd4# 0–1 Miles,A -De Firmian,N Manila 1990

A modern classic!

Back to Bogolyubow-Alekhine!

9.e4 0–0 10.Bf4 Qb6 11.Rd1 Ne8 12.Ne2 d6 13.Be3 Qc7 14.Nd4

All Black’s opening moves (4…c5, 6…Bxc3+, 8…a5) have left horrible holes that White’s pieces will gratefully exploit. Alekhine goes for violent struggle instead of passive defence but Bogolyubow is up to the task!

14…Qe7 15.Nb5 Ra6 16.Be2 f5 17.e5 dxe5 18.Qxe5 Nd7 19.Qc3 e5 20.0–0 Rg6 21.Qxa5 f4 22.Bc1 Qg5 23.Rf2 e4 24.fxe4 Ne5 25.Qd8 Nf6 26.Bxf4 Nf3+ 27.Bxf3 Qxf4 28.Qd6 Qh4 29.g3 Qh3 30.e5 h6 31.Bd5+ Kh7 32.Qxf8 Nxd5 33.cxd5 Bg4 34.Rd3 Qh5 35.Nd6 Be2 36.Nf7 Rb6 37.Rd2 Bc4 38.Qc5

1–0

Alekhine reacted well with a beautifully-played queenless middlegame win in the 5th game that made it into his Best Games Collection! However, the pattern of the 4th game repeated itself in the 6th game. Another experiment from Alekhine, another response of controlled aggression from Bogolyubow, and this time a long, painful downhill slide for Alekhine.

Things were looking up for Bogolyubow! A potentially disastrous start to the match turned around into parity after 6 games and already 2 good wins against the World Champion! That makes it all the harder to understand what happened in the 7th and 8th games. I have the strong suspicion that the effort of playing a 21-round tournament just before the match started to take its toll. From a good position in the 7th game, Bogolyubow – uncharacteristically – blundered his position away in one move:

Alekhine,Alexander – Bogoljubow,Efim

World Championship 1929, 7th game

20.f6

Bogolyubow had missed a chance a couple of moves earlier to get an easy advantage with no risk, but he’s still perfectly fine

20…Rxe3

Throwing the game away

20…exf6 21.Rae1 (21.Bc5 given by Winter and Yates as winning is unfortunately met by 21…Re5 winning a piece) 21…Qe5 22.Qxe5 (22.Rf5 Qc3) 22…Rxe5 23.Bf4 is balanced: White’s 2 bishops compensate for Black’s 2(!) extra pawns

21.Qg5 Rxg3+ 22.Qxg3 exf6 23.Rad1

Black has 3 pawns for the exchange but his pieces are awful and his king’s position is very weak.

23…Kh8 24.Kh1 Bh6 25.Qd6 Bg7 26.Qe7 Qe5 27.Qxb7 f5 28.Rde1 Qf6 29.Qf3 Qc3 30.Qxf5 Nc8 31.Bc2 Qc6+ 32.Rf3 Qg6 33.Qxg6 hxg6 34.Bxg6 Kg8 35.Bxf7+

1–0

In the 8th game, Alekhine again played riskily and experimentally with Black but this time Bogolyubow looked jaded – maybe a little depressed after the previous game – and played very poorly, putting his pieces on second-rate squares while leaving himself exposed by expanding in the centre. Alekhine doesn’t just punish – he annihilates!

Bogoljubow,Efim – Alekhine,Alexander

World Championship 1929, 8th game

1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 b6 3.Nc3 Bb7 4.f3 d5 5.cxd5 Nxd5 6.e4 Nxc3 7.bxc3 e6 8.Bb5+ Nd7 9.Ne2 Be7 10.0–0 a6 11.Bd3 c5 12.Bb2 Qc7 13.f4 Nf6 14.Ng3

Bogolyubow has played a little strangely, placing his bishop on the passive square b2 (e3 would be more natural) and advancing f3–f4 a little early. Alekhine’s reaction is brutal!

14…h5

This reminds me of Alekhine’s play in the 17th game of this match. There also, he generated confusion in the position by chasing after a knight with a rook’s pawn at an early stage of the game

Alekhine,Alexander – Bogoljubow,Efim

World Championship 1929, 17th game

1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 g6 3.f3 d5 4.cxd5 Nxd5 5.e4 Nb6 6.Be3 Bg7 7.Nc3 Nc6 8.d5 Ne5 9.Bd4 f6 10.f4 Nf7

I’m sure you can guess what happened!

11.a4 e5 12.dxe6 Bxe6 13.a5 Nd7 14.a6 b6 15.Bb5

with a massive position for White

Back to the main game!

15.Qe2 h4 16.Nh1 Nh5 17.Qg4 0–0–0 18.Rae1 Kb8 19.f5 e5 20.d5 c4 21.Bc2 Bc5+ 22.Nf2 g6 23.fxg6 Rdg8 24.Bc1 Bc8 25.Qf3 Rxg6

Fantastic mobilisation of his forces by Alekhine! EVERYTHING is attacking! Bogolyubow has been unrecognisable in this game.

26.Kh1 Ng3+ 27.hxg3 hxg3+ 28.Nh3 Bxh3 29.gxh3 Rxh3+ 30.Kg2 Rh2#

0–1

Bizarrely enough, the 1934 match between Alekhine and Bogolyubow saw an almost identical scenario. After a desperately disappointing 8th game for Bogolyubow in which he threw away a win on the 56th move, Alekhine played the 9th game in a very unorthodox manner:

Bogoljubow,Efim – Alekhine,Alexander

World Championship 1934, 9th game

1.d4 c5 2.d5 e5 3.e4 d6 4.f4 exf4 5.Bxf4 Qh4+

6.g3 Qe7 7.Nc3 g5 8.Be3 Nd7 9.Nf3 h6 10.Qd2 Ngf6 11.0–0–0 Ng4 12.Be2 Bg7 13.Rhf1 Nxe3 14.Qxe3 a6 15.Ng1 b5 16.Rde1 Bb7 17.Nd1 0–0–0 18.Bg4 Kb8 19.Bxd7 Rxd7 20.Qd2 g4 21.Ne3 Qe5 22.c3 h5

Again Bogolyubow played very weakly and lost without a fight.

Back to 1929! After the 8th game, the match was adjourned for 2 weeks which was probably a welcome respite for Bogolyubow! The rest of the match proceeded along a similar pattern with Alekhine steadily increasing his advantage though never able to pull away completely – he lost 3 more games until the end of the match! We’ll take a look at the highlights of games 9-25 in future blog posts!

Dear Mr. Sadler It appears that game “1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 g6 3.f3 d5 4.cxd5 Nxd5 …” should be given number 17 as stated in the introduction in game 8. Looking forward to games 9-25. Thank you for the instructive notes and access to your pages! Best regards Peter Rutz

Hi Peter, thanks for your comment! Well spotted – I’ve corrected that now! Glad you’re enjoying the series! Best Wishes, Matthew