I was saddened to hear last week that the great Russian trainer Mark Dvoretsky had died at the age of 68. As a tribute, I wanted to share my experiences of studying with Mark in the mid-90’s. I got the opportunity to do so while my friend (and former coach) Steve Giddins was working in Moscow. Steve organised everything, gave me a place to stay, fed me and encouraged me and I will be forever grateful to him for doing so! I’m also enormously grateful to my parents for sponsoring me as always!

The first session came at a low point in my career. I had secured the grandmaster title in 1993 (at the almost-past-it age of 19). I had hoped that I would progress quickly after the appalling stress of securing the title had passed, but that hadn’t happened. I had given up the notion of becoming World Champion many years ago, but now I was wondering whether I would ever even make it to 2600.

Before the training, I was both sceptical and anxious. Firstly, sceptical. Mark hadn’t been an active player for many years: could he really teach me anything about the modern game? Secondly, anxious. How could a trainer who had worked with the finest talents in the world find any motivation in working with a 20-year old struggling with a rating in the mid-2500’s?

The sessions turned out to be the best experience of my professional career and that was due in no small part to Mark’s kindness and patience. In the first set of puzzles he gave me in order to evaluate my strength, I failed to solve a position that a 12-year-old Kramnik had cleared up in 15 seconds. What a way to start: I was mortified and so ashamed, I felt I’d made a complete fool of myself. I think that many coaches couldn’t have resisted the temptation to indulge their talent for sarcasm and turn this into a running joke, but that wasn’t in Mark’s character. He explained the position clearly to me, demonstrated Kramnik’s solution (as well as the less successful efforts that other players had made, which made me feel a bit better!) and tailored the training that week to strengthen the weakest areas of my game.

The pace of the training was relentless. The days were pretty intensive, but I particularly remember the long nights I spent struggling to get to grips with the homework that Mark had set me. Ah, the thrill I felt though when the solutions I found turned out to be correct!

If you ask me what I learned from Mark in those sessions, then you’ll get a rather strange answer. I’m sure that I benefited from learning technical aspects (such as “The Superfluous Knight” or “Prophylaxis”) straight from the master but that’s not the most important thing; it would have taken me longer, but I could have picked up those concepts myself through studying Mark’s books. The fantastic thing about working with Mark was that I grew to understand myself and my level of play much better after those sessions. Testing myself against the fantastic chess material in his library, hearing from Mark which of his pupils had solved particular positions and which hadn’t, and getting clear and honest feedback when my solutions fell short gave me a complete picture of both my weaknesses and my strengths. Crucially for me, I gained confidence that my strengths might make me dangerous at a higher level, even if there was still plenty of work to do on other parts of my game. Mark created a safe and motivated environment filled with wonderful technical material in which this sort of learning experience could take place.

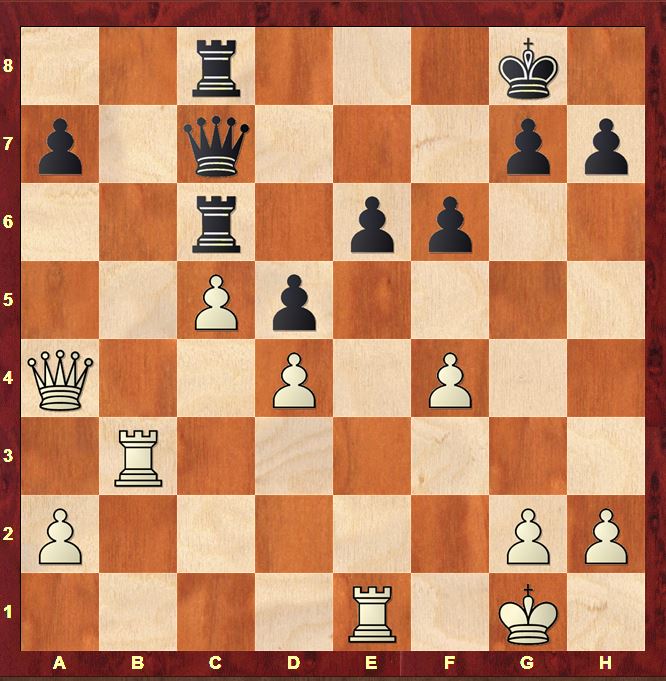

The first session has one particularly memorable moment: it was a real turning point for me, a moment in which I suddenly believed again that I could still become a strong player. Mark had set me another series of puzzles as homework and this position interested me greatly:

Hort,Vlastimil – Mestel,A Jonathan

Lloyds Bank 1982

The task was to keep control of the position. In particular, White must watch out for potential Black counterplay with …e5. In the game, Hort found a careful and controlled approach. I found something…not those things!

25.g3

25.Rf3 Qb7 26.Qd1 was Hort’s approach, protecting all his exposed points (d4 and f4) without creating additional weaknesses. Having absorbed Black’s counterplay, his next goal is to exert pressure on e6. It works very smoothly in the game. It’s possible that Black should have protected e6 multiple times and played …f5 to stop f4–f5 coming once White has tripled on the e-file, but that would deprive Black of his counterplay with …e6–e5: mission accomplished for White! The game ended:

26…Ra6 27.Rfe3 Qd7 28.Qe2 Ra4 29.Rxe6 Rxd4 30.c6 Qf7 31.Re8+ Rxe8 32.Qxe8+ Qf8 33.Qxf8+ 1–0

25…e5

When I showed 25.g3 to Mark, he looked a little disappointed and whipped out 25…e5 straightaway. He stopped when I made my next move

26.Rbe3

was my concept. I had only looked briefly at taking on e5, as I didn’t think allowing counterplay on the f-file was very sensible

26…exd4

The only test. 26…e4 27.Rb3 is the first clever point. The …e5 break has passed and White’s structure is still intact: White is ready to invade on the b-file without fear of central counterplay.

27.Re7 Qb8

27…Qd8 28.Re8+ wins

28.Qd1

I was getting quite excited at this point: it felt a little like unleashing an enormous novelty!

28…Kh8

Mark found this defensive idea very quickly. I’d been somewhat slower in my analysis, but I’d found a good reply

29.Qh5

29…Rg8 30.Rxg7

Bang! Mark liked this! It’s not completely winning unfortunately!

30…Rxg7 31.Re8+ Rg8 32.Rxb8 Rxb8 33.Qxd5 Rbc8 34.Qxd4 R8c7

was my line, with an edge for White. However, Komodo points out

34.Qf7 d3 35.Kf2 Rxc5 36.Qxf6+ Kg8 37.Ke3 which indeed looks much stronger!

After we’d played out the moves on the board, Mark told me that none of his students had come up with that solution before. That was the first time I’d managed to do that, and the pride I felt then has stayed with me to this day.

I only studied with Mark for 2 weeks in total, so it feels presumptuous to call myself a pupil of his, but in terms of the effect and influence he had on my chess strength and chess thinking, I can truly call him my teacher. He will be greatly missed.

Wonderful story Matthew – and a real insight into the workings of this brilliant teacher. I have many times, over the years, wondered if our top English players would benefit from a Dvoretsky training session, such was the esteem in which his methods were generally held. Little did I know!

Congratulations on the ECF Book of the Year award by the way. It is a uniquely educational, and yet entertaining read. And I disagreed with their light criticism of the choice of Capablanca – you were simply encouraging us to pick someone inspirational as a tool, to help rekindle the passion after a lull in activity – not adding him as one of your role models! I should have thought that was clear!

Hi Colin, thanks for your comments! Glad that you liked the story about Mark – he really was a quite remarkable teacher! I did understand the criticism about the book as I seriously considered using Lasker as a role model (he is a fantastic example of longevity) However, John Nunn had written such a good book about his play (“John Nunn’s Chess Course”) I didn’t think I could possibly add anything new! And indeed, Capablanca’s play inspires me so much, I hoped it would inspire others too! Best Wishes, Matthew