I recently managed to get hold of a copy of the 1930 book “Games Played in the World’s Championship Match between Alexander Alekhine and E. D. Bogolyubow” with annotations by F.D Yates and W. Winter.

It’s one of those World Championship matches that I’ve never paid much attention to. The final score of 15,5-9,5 is pretty convincing and seems to reflect the enormous gap in strength between Alekhine and his challenger.

However, reading through this book and playing through the 25 games, I developed a healthy respect for Bogolyubow’s performance during the match. In many ways, its course reminded me of my favourite World Championship Match of recent years: the match between Garry Kasparov and England’s Nigel Short in 1993. In that match, the challenger also played enterprisingly and consistently set a seemingly invincible opponent very severe problems. However, just like Kasparov, Alekhine displayed exceptional resiliency at crucial moments and managed to keep his challenger at a safe distance throughout the whole match. In fact, Alekhine’s performance set the record for the most wins scored in a single World Championship Match (11)

I’ll take a look at this match over the course of a few blog postings. In this article, I’ll give an overview of the match and take a brief look at the openings choices of both players.

Overview of the match

The score

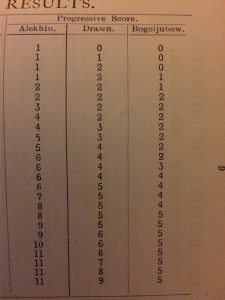

Alekhine started the match very impressively and could have been 3-0 up after 3 games! After his crushing win in the 1st game (analysed in an earlier Blog article http://matthewsadler.me.uk/chess-for-life/alekhines-themes-move-like-morphy/) Alekhine came very close to winning the next 2 games but faltered both times in the late stages of the endgame. The next 5 games witnessed the first flurry of punches with 5 decisive results which Alekhine won 3-2 thanks to a strange blunder by Bogolyubow in a pleasant position in the 7th game. Bogolyubow played quite poorly the next game so the 7th game may have had a double effect on the match.

A couple of calm, impressive wins with Black by Alekhine in the 10th and 12th games were undone by some nervy play in the 13th and 14th games. In the first of these, Alekhine failed to capitalise on a promising novelty and blundered a piece on the 31st move, a loss that he followed up by failing to hold a very slight disadvantage in a rook and opposite-coloured bishop ending.

Once again however, Alekhine showed his resilience and scored 5 wins (and just 1 loss) in the next 7 hard-fought games to keep himself on track. Bogolyubow never gave up, but 3 tough draws secured the title for Alekhine.

The locations

The match was played in 6 different locations in Germany and Holland:

| Rounds | Location | From…To… | Score at the end |

| 1-8 | Wiesbaden, Germany | 6th Sep 1929 -19th Sep 1929 | 5-3 to Alekhine |

| FIDE Congress | Venice Italy | 26th Sep – 30th Sep 1929 | Alekhine represents France at FIDE congress |

| 9-11 | Heidelberg, Germany | 3rd Oct 1929 – 7th Oct 1929 | 7-4 to Alekhine |

| 12-17 | Berlin, Germany | 11th Oct 1929 – 21st Oct 1929 | 10,5-6,5 to Alekhine |

| 18-19 | The Hague, The Netherlands | 26th Oct 1929 – 27th Oct 1929 | 11,5-7,5 to Alekhine |

| 20 | Rotterdam, The Netherlands | 30th Oct 1929 | 12-8 to Alekhine |

| 21-22 | Amsterdam, The Netherlands | 1st Nov 1929 – 3rd Nov 1929 | 14-8 to Alekhine |

| 23 | The Hague, The Netherlands | 5th Nov 1929 | 14,5-8,5 to Alekhine |

| 24-25 | Wiesbaden, Germany | 10th Nov 1929 – 11th Nov 1929 | 15,5-9,5 to Alekhine |

The openings

Bogolyubow as White

Bogolyubow opened 8 games (his first 8 White games) with 1.d4 and finished off the match with 1.e4. He almost held his own with this colour over the course of the match:

| Opening | Win | Draw | Loss |

| 1.d4 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| 1.e4 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

It’s interesting to focus a little more deeply on Alekhine’s responses to both of Bogolyubow’s opening moves:

| Alekhine’s openings vs 1.d4 | Win | Draw | Loss |

| 1…Nf6 Nimzo-Indian | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 1…Nf6 2…b6 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1…d5, 2…c6 to Cambridge Springs | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 1…d5, 2…c6 to Meran 5.Bd3 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

As you can see, the battleground on the 1. d4 openings shifted quite regularly. Alekhine started off defending the Nimzo-Indian to which Bogolyubow consistently replied 4.Qb3.

This was one of the main continuations at the time and Bogolyubow was very successful with it. I am a little mystified by Alekhine’s tactics in this opening. In the 2nd game, he played the conventional 4…c5 5.dc Nc6 and achieved a very comfortable game which he almost converted into a win with excellent and riskless play. In the next couple of games however, he switched to an experimental mode with 4…c5 5.dc Na6 and 4…Qe7 5.a3 Bxc3+ 6.Qxc3 b6. Bogolyubow reacted identically in both cases by stifling Alekhine in the centre with f3 and e4 and won 2 fine games. For example, the 4th game reached this position after 11 moves:

It wasn’t a very practical approach from Alekhine and he continued this trend in the next game with the very dubious 1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 b6.

This seemed however to confuse Bogolyubow – possibly still reeling after a bad blunder in a promising situation in the 7th game – who placed his pieces very poorly and was swept away and mated in 30 moves.

The match was now adjourned for 2 weeks(!) while Alekhine represented France at the FIDE congress of 1929 in Venice, and the character of the match changes completely. Alekhine switched to more solid openings against 1.d4: the Cambridge Springs via the Slav move order – 1…d5 2.c4 c6 2.Nf3 Nf6 4.Nc3 e6 5.Bg5 Nbd7 6.e3 Qa5

and the Meran 1…d5 2.c4 c6 3.Nf3 Nf6 4.e3 e6

Bogolyubow was pretty innovative at this stage, introducing an important novelty in the Cambridge Springs – 7.cxd5 Nxd5 8.Qd2 – which is still very topical to this day:

and using an interesting move order against the Meran: 5.Bd3, avoiding an early Nc3 which he’d never used previously (Alekhine himself had played 3 games in 1926 on the White side of this line!)

However, he obtained a relatively meagre reward for his efforts scoring only 1/4.

In the last phase of the match Bogolyubow switched to 1.e4 against which Alekhine looked much less solid, in particular in the French Defence. Honours were shared in Bogolyubow’s last 4 White games.

| Opening vs 1.e4 | Win | Draw | Loss |

| 1…e6 – French | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 1…e5 – Lopez | 0 | 1 | 1 |

Bogolyubow as Black

| Opening | Win | Draw | Loss |

| 1.d4 | 1 | 6 | 6 |

Unlike Bogolyubow, Alekhine stuck to 1.d4 throughout the match. Bogolyubow used a number of defences:

| Bogolyubow openings vs 1.d4 | Win | Draw | Loss |

| 1…d5 2…c6 4…dc Slav | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 1…Nf6 2…g6 KID / Grunfeld | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 1…d5, 2…c6 to Cambridge Springs | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| 1…Nf6 Nimzo-Indian | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1…d5, 2…c6 to Meran 5.Bd3 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

The Slav led to a very bad start for Bogolyubow with the Black pieces.

The 1st and 5th games made it into Alekhine’s collection of Best Games while Bogolyubow was incredibly lucky to escape with a draw in the 3rd game. Bogolyubow therefore ventured 1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 g6 in the 7th game. Alekhine’s 3.g3 was not particularly successful which must have made Bogolyubow’s blunder in a good position all the more vexing for him.

Bogolyubow clearly also put his 2 weeks’ break to good use, introducing the Cambridge Springs into his repertory to replace the rather battered Slav. And here a rather bizarre part of the match started. Take a look at this selection of openings in the 1.d4 games in the second half of the match:

| Game | White | Black | Opening | Interesting points |

| 9 | Alekhine | Bogolyubow | Cambridge Springs | 7.Nd2 |

| 10 | Bogolyubow | Alekhine | Cambridge Springs | 7.Nd2 |

| 12 | Bogolyubow | Alekhine | Cambridge Springs | 7.cxd5 Nxd5 8.Qd2 (a novelty) |

| 13 | Alekhine | Bogolyubow | Cambridge Springs | 7.cxd5 Nxd5 8.Qd2 |

| 14 | Bogolyubow | Alekhine | Meran | 5.Bd3 (unusual move order) |

| 16 | Bogolyubow | Alekhine | Meran | 5.Bd3 (unusual move order) |

| 23 | Alekhine | Bogolyubow | Meran | 5.Bd3 (unusual move order) |

| 25 | Alekhine | Bogolyubow | Meran | 5.Bd3 (unusual move order) |

| 21 | Alekhine | Bogolyubow | Nimzo-Indian | 4.Qb3 (the same variation as Bogolyubow played with White in the 2nd, 4th and 6th games!) |

It seems as if both players were stealing ideas from the other in their 1.d4 openings!

Additionally, Alekhine also introduced a couple of original opening ideas:

3.f3 against the KID / Grunfeld

This had been introduced into top-level play just a few months before in the game Nimzowitsch-Tartakower and it gave Alekhine a much sharper weapon than the 3.g3 he had tried in the 3rd game.

6.e4 against the Cambridge Springs

Strangely enough, first played by Napier against Teichmann …at the Cambridge Springs tournament of 1904! Alekhine gave the line a special twist in the 19th game by castling queenside!

There’s just one little mystery that I can’t explain to myself. In the 11th game, Bogolyubow apparently played (with Black) 1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 c6 3.Nc3 e6…

…and Alekhine apparently didn’t play 4.e4! I just can’t believe that!

That’s all for this time. In a following blog posting, I’ll take a look at some interesting moments from the games!