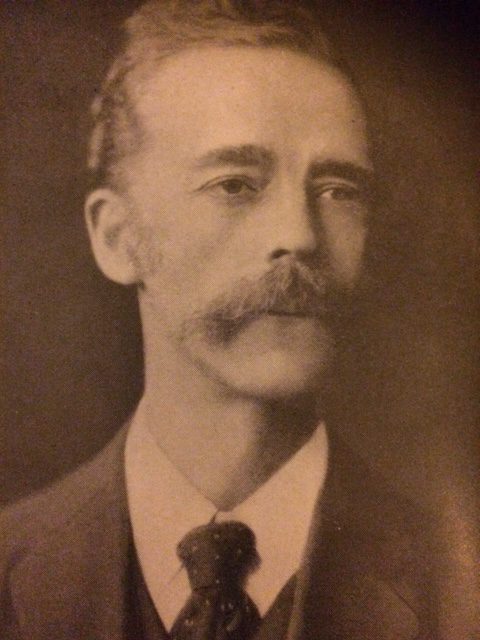

After my series on 6-times British Champion F.D. Yates, my friend Steve Giddins suggested that I look at the games of one of the 2 players to have exceeded Yates’ record of British Championships: H.E. Atkins (1872-1955), 9-times British Champion (as Steve Giddins pointed out, Jonathan Penrose is the record-holder with 10 victories between 1958 and 1969). I knew a little about Atkins thanks to the tournament book of the 1899 Amsterdam amateur tournament. On his international debut, Atkins won all 15 games, finishing 4 points ahead of an assortment of the leading Dutch players, one of whom was Arnold van Foreest – a forebear of the young Dutch GM Jorden van Foreest. The gulf in class was so great, it was difficult to assess how strong Atkins really was. However, Steve pointed me to the chessbooks.co.uk site where a copy of R.N Coles’ “H.E. Atkins, Doyen of British Chess Champions” was available.

Coles provides a short biography of Atkins and annotates 50 selected games between 1893 and 1937 which gives a more complete picture of Atkins’ style and strength.

Although Atkin’s chess career spanned more than 50 years, he played little. Megabase 2017 only contains 230 of his games. In comparison, F.D Yates is represented by 803 games in a much shorter period. The difference was that Atkins was a true amateur. A schoolmaster by profession – Mathematics Master at 2 schools between 1892 and 1909 and then Principal of Huddersfield College from 1909-1936 – he had long periods of absence from tournament chess. Between 1911 and 1922, and between 1927 and 1935, he played no tournament chess, confining himself to local matches. However, every time he re-emerged, his results were impressive.

His first outstanding result was 3rd place in the extremely strong 1902 Hanover Tournament, finishing behind Janowsky and Pillsbury but ahead of a field including Chigorin, Marshall, Gunsberg and Mason. 20 years later, we see Atkins taking on the star-studded field of the 1922 London International Tournament (Capablanca, Alekhine, Rubinstein and Bogolyubow amongst others). He finished just outside the prizes (“for the only time in his chess career” according to Coles) but beat Rubinstein and Tartakower in 2 sparkling games. In 1937, Atkins played his last major tournament, finishing =3rd in the British Championship at the age of 65. He was awarded the IM title in 1950.

I’ve been extremely impressed by Atkins’ play. I liked his uncomplicated opening play with White and his willingness to take on typical pawn structures such as the Isolated Queen’s Pawn (IQP) and Hanging Pawns. He also shows a touch of class in the way he coordinates his forces in the heat of battle. His marshalling of forces around an active queen in his games against Rubinstein and Prins made a big impression on me and inspired me directly in a tense game at the recent 4NCL weekend in March.

In the next couple of articles, I’d like to examine 3 of Atkins’ games: his win against Rubinstein from the 1922 London tournament, his victory against his lifelong rival F.D. Yates in the British Championship playoff of 1912 and his defeat of the Dutch player Prins in the England-Holland match of 1937 when Atkins was already 65!

The game Rubinstein lost against Atkins at London 1922 was notable for an unusual reason: at the closing ceremony at the Central Hall, Westminster, Canon A.G. Gordon Ross presiding said that the “big four” – Capablanca, Alekhine, Vidmar and Rubinstein – had played 48 games against all the other masters in the tournament and won 33, drawn 14 and lost just one. That one loss was to Atkins! (Yorkshire Post, 21st August 1922)

A little historical digression. The London 1922 congress was opened by no less than Bonar Law, a couple of months before he became Prime Minister. He gave a well-received speech which was reported extensively in the Western Daily Press of 1st August 1922. A few soundbites!

“Chess was the king of games (Applause).

When he first became a member of the House of Commons, he looked to the front benches and wished someone would invent a machine with which to measure accurately the mental ability of every member (Laughter). Later he felt that was the last thing he would desire (Laughter). Successful chess playing required the power of seeing further than one’s opponent. It required the power of concentration. It required a great deal of imagination, patience and vigilance. Chess was a jealous mistress and anyone who really mastered the game had very little energy left for anything else.

It might be said by some that chess was a waste of human energy, but no form of human energy was ever wasted (Hear, hear). There was tremendous scope for chess and he only wished it was more popular in this country.

He trusted the public would realise that chess was a game worth patronising and worth playing (Applause)”

Enough history for now! Let’s look at some chess! The game is available again in playable form at http://cloudserver.chessbase.com/MTIyMTYx/replay.html

Atkins,Henry Ernest – Rubinstein,Akiba

London 1922

1.d4 Nf6 2.Nf3 e6 3.c4 d5 4.Bg5 Nbd7 5.e3 Be7 6.Nc3 0–0 7.Bd3

An example of Atkins’ uncomplicated opening play with White. As Coles comments, “At this date the chess world was becoming conscious of the ‘fight for the tempo’ in this opening, and it was, therefore, usual to defer development of this bishop in the hope of recapturing on c4 in one move. Atkins disdains such slender and doubtful finesses”

7…dxc4 8.Bxc4 a6 9.a4 c5 10.0–0 Qa5

An unusual move from Rubinstein, but not a bad one. Black activates his queen – aiming at White’s weakened queenside squares such as the pawn on a4 and the b4 square – before saddling White with an IQP. Moving the queen from d8 allows Black to connect his rooks and prepares the solid manoeuvre …Bd7–e8, strengthening the f7 square – very prudent against Atkins seeing his previous games in this structure!

11.Qe2 cxd4 12.exd4

Atkins was always happy to take on the attacking side of the IQP. He scored 2 quick wins at the Amsterdam 1899 tournament with this structure: against Pelzer in 25 moves, and against Te Kolste in 19 moves, both times sacrificing a knight on f7!

12…Nb6 13.Bd3 Rd8 14.Rfd1 Bd7 15.Ne5

15.Bxf6 Bxf6 16.Qe4 is a sharp win of a pawn: 16…g6 17.Qxb7 Black’s 2 bishops and the weakness of White’s queenside feels like compensation

15…Be8 16.Qe3

This is so risky, I’m tempted to believe that it was a tactical oversight! Atkins wants to bring his queen to h3 but he must have missed Black’s next idea.

16…Nfd5 17.Qg3

Atkins misses the fantastic justification of 17.Qh3 and enters into fairly speculative territory. 17.Qh3

is the first move you look at, but White’s attack looks very unconvincing after 17…Bxg5 18.Qxh7+ Kf8 19.Qh8+ Ke7 20.Qxg7 Bf6 21.Ng6+ Kd7 and the king escapes to the queenside. However, Komodo comes up with 18.b4.

I only vaguely grasped what he was up to! The major virtue of 18.b4 is that it is extremely forcing: to rescue his queen, Black can choose out of 2 recaptures. I can’t take any credit for any of the ensuing variations!

a) 18…Nxb4 19.Qxh7+ Kf8 20.Qh8+ Ke7 21.Qxg7 Bf6 22.Ng6+

The deflection of the knight from d5, has unprotected the bishop on f6!

22…Kd7 23.Qxf6 fxg6 24.Rab1 Nxd3 25.Rxd3 Kc7 26.d5

It still looks very murky to me, but Komodo sees a clear advantage for White

b) 18…Qxb4 19.Nxd5 Rxd5

19…Nxd5 20.Qxh7+ Kf8 21.Rab1

is very unpleasant for Black. Once the White rook comes to b7, Black’s escape square for his king is cut off!

21…Qxa4

Attacking the rook on d1

22.Bc2 Qa5 23.Rxb7

Threatening Qh8+ mate

23…Nc7 24.Qh8+ Ke7 25.Qxg7 Bf6 26.Ng6+ Kd7 27.Qxf6 fxg6 28.Rc1 Rdb8 29.Ba4+

wins according to Komodo

20.Rab1

20…Qd6 21.Qxh7+ Kf8 22.Qh8+ Ke7 23.Qxg7 Bf6 24.Ng6+

Again the destruction of the knight on d5 leaves Black’s bishop on f6 unprotected

24…Kd7 25.Qxf6 fxg6 26.Be4

Again seems very murky to me, but Komodo sees a definite advantage for White. Amazing tactics!

Back to Atkins’ 17.Qg3!

17…Bxg5 18.Qxg5

Black has the possibility of …f6 winning a piece, either before or after …Nxc3. Amazingly, White seems to have just enough to keep the balance!

18…Nxc3

18…f6 19.Qh4 fxe5 20.Qxh7+

20.Bxh7+ Kf8 21.Rd3 is mentioned in the tournament book according to Coles, but refuted (correctly) by him with 21…Nf4

20…Kf8

20…Kf7 21.Bg6+ Kf6 22.Ne4+

21.Qh8+

a) 21…Ke7 22.Qxg7+ Bf7 23.Bg6 Rf8

a1) 24.dxe5 is strong but not completely clear

24…Rac8 25.b4

My line. I really should have spotted this idea earlier!

25…Qxb4 26.Nxd5+ Nxd5 27.Rxd5

27.Rab1 was what I really wanted to play

a) 27…Qa5 28.Rxb7+ Rc7 29.Rb8 A gorgeous tactic!

b) 27….Qf4 28.Rxb7+ Rc7 29.g3 Qg5 (29…Qf3 30.Rd3) 30.Rb8 Again!

c) 27…Qc5 28.Rxb7+ Rc7

though Komodo still prefers White after

29.Rxc7+ Qxc7 30.h4

Back to 27.Rxd5

27…exd5 28.Qf6+ Kd7

28…Ke8 29.Bxf7+ Rxf7 30.Qe6+

29.Bxf7 is very strong for White

a2) 24.Ne4

is suggested by Coles and is indeed even more powerful

24…Nc4 25.Ng5 Nd6 26.dxe5 Ne8 27.Qh7 Ndf6 28.exf6+ Nxf6 29.Qh6 Ng4 30.Qh5

was my line.. and Komodo’s #1 line too! White is winning

b) 21…Kf7 22.Ne4

was Atkins’ suggestion and it seems to be winning. Ng5+ followed by Qf8+ is a massive threat

22…Rd7 was the best Komodo could come up with

23.dxe5 Ke7 24.Nd6 Rxd6 25.Qxg7+ Kd8 26.exd6 Qb4 27.a5 Nc8 28.Rac1

is awful for Black according to Komodo

19.bxc3 Nd5

19…f6 isn’t mentioned by Coles but looks a much more sensible attempt for Black as White’s knight on c3 was a powerful reinforcement of the attack

20.Qh4 fxe5 21.Bxh7+ Kf8 22.Rd3 Rd7

looked pretty speculative to me. Komodo thinks equal!

23.Re1 Rxd4 24.Rxd4 exd4 25.Rxe6 Nd5 26.Bf5 Qxc3 27.Qh8+ Kf7 28.Qh5+

with a draw by repetition was one line I came up with and Komodo finds it fairly plausible.

With 19…Nd5, Rubinstein doesn’t want to force a crisis yet and brings defensive pieces towards the kingside. He perhaps unwittingly triggers a number of tempting tactical possibilities, none of which seem to work however.

20.Qh4

a) 20.Nxf7 excited me for a little while but Komodo’s 20…Kxf7 21.c4 exploiting the pin along the 5th rank! 21…h6 22.Qe5 Qc7 neutralises this idea effectively

b) 20.c4 h6 (20…Nf6 21.Nxf7 is the idea!) 21.Qg4 Nb4 looks reasonable for Black

c) 20.Bxh7+ Again got me excited, but White has too few pieces left to cause too much trouble 20…Kxh7 21.Rd3 f6 22.Qh4+ Kg8 23.Rh3 fxe5 24.Qh8+ Kf7 25.Rh7 Ke7 26.Qxg7+ Kd6 27.c4 Rd7 28.Qf8+ Kc7 29.Rxd7+ Kxd7 30.cxd5 which Komodo sees as leading to a draw. Just as with 19…f6, it feels as if White is having to show all the ingenuity to keep his position together!

20…Nf6 21.c4 h6

Rubinstein has played the middlegame conservatively, and White has reached a pleasant Hanging Pawns structure. I was very impressed with the calmness of White’s next few moves. Understanding that the time is not yet ripe for an all-out kingside assault, Atkins cleverly consolidates and strengthens his position. In this coming phase of play, the White queen is the pivot of White’s position.

22.Qg3 Rac8 23.Bc2 Bc6 24.Qe3

White has covered his a4 pawn with his bishop and his d4 pawn and queenside dark-squares with his queen on e3. This consolidation convinces Rubinstein to remove a defensive piece from the kingside (the bishop on e8) and place it more aggressively on the a8–h1 diagonal.

24…b6

24…Nd7 25.Nxf7 Kxf7 26.d5 exd5 27.cxd5 Bxd5 28.Rxd5 Qxd5 29.Bb3 Rc4

Hadn’t spotted that one!

30.Rd1 Qe6 31.Qxe6+ Kxe6 32.Bxc4+ is sort of equal

25.Ra3 Ba8 26.Qf4

Another lovely queen move, moving a step closer to the kingside, eyeing the f7 square which is no longer defended by Black’s light-squared bishop and freeing the 3rd rank for the rook on a3 to move to the kingside. As John Nunn once remarked, “A rook on the third rank plus a queen is very often a decisive force even without additional assets”

26…b5

Rubinstein takes immediate action, trying to break the barrier posed by White’s hanging pawns in order to generate counterplay

27.Rh3

27.Rg3 Kf8

is tough to break. I had thought of

a) 28.Bg6 Rxc4 A typical sacrifice that we shall see many times in the ensuing variations (28…fxg6 29.Rxg6 is the nice idea) 29.Nxc4 bxc4 is a little embarrassing for White as the retreat of the bishop allows 30.Bc2 Nh5

b) 28.Rh3 Rxc4 29.Nxc4 bxc4 looked balanced to me: Komodo agrees.

27…bxc4

I would have played 27…Rxc4 28.Nxc4 bxc4 in a flash!

Black looked basically OK to me with a pawn for the exchange, a passed c-pawn, some solid central squares and some White queenside weakness to aim at and Komodo agrees giving White just a tiny edge. Rubinstein’s choice is extremely risky.

28.Rxh6

This was where my fun train analysis started!

28…Rc5

a) 28..gxh6 29.Qxf6 Qc7 30.Re1 followed by Re3–g3 wins

b).28..Rxd4

Not mentioned by Coles. Amazingly White doesn’t have a direct win

29.Bh7+

My line. I thought that 29.Qxd4 gxh6 30.Qf4 Rd8 was just fine for Black. Komodo proposes 31.Rxd8+ Qxd8 32.h4 Kg7 33.g4 with an initiative, but Black has reasonable defensive chances

29…Kf8 30.Qxd4

30.Ng6+ fxg6 31.Qxd4 lovely idea but 31…Qd5 ruins everything (31…Qg5 32.Qd6+)

30…gxh6 31.Nd7+

31…Nxd7 32.Qh8+ Ke7 33.Qxc8 Bd5

was my main line. It’s a bit better for White but tricky to convert as Black is well-centralised and active.

Rubinstein’s 28…Rc5 is tricky but just doesn’t feel right!

29.Rh3

A very sensible idea, preparing Qh4 but as Coles correctly points out, Black can now confuse matters enormously.

I had thought that 29.Rh8+ Kxh8 30.Nxf7+ Kg8 31.Nxd8 was winning but I’d missed a very nasty retreat…

31…Rc8

The knight is trapped! 31…Rg5 32.Qb8 Rxg2+ 33.Kf1 Qd5 34.Nxe6+ Kf7 35.Qf8+ Kxe6 36.Re1+ was the line I was counting on

32.Nxe6 Qd5

29…Rcd5

Rubinstein misses his chance!

29…Be4

Mentioned by Coles and definitely best

30.Qh4

30.Bxe4 Rxe5 as the bishop on e4 has been deflected from the defence of the rook on d1

30…Kf8

I was wondering how to hold White’s position together but Komodo points out

31.Qxe4 Nxe4 32.Rh8+ Ke7 33.Rxd8 Rxe5 34.dxe5 Qxe5 35.R8d7+ Kf6 36.Bxe4 Qxe4 37.Rc1 Qc6 38.Rd4 c3 39.Rd3 Qxa4 40.Rdxc3 when Black should not be able to hold his a-pawn after Rb1, Rcc1, Ra1 and then doubling on the a-file.

After you see 29.Rh3 Be4, you may understand why Komodo’s 29.Rh5 is such a gorgeous move!

Black’s counterplay after …Rc5 is all based on the blow …Rxe5. The text deals with this and prepares both Rg5 increasing the pressure on Black’s kingside and the simple h3 removing any back-rank threats (which means the Black rook is no longer safe on c5).

30.Kf1

30.Qh4 Kf8 31.Qh8+ Ke7 32.Ng6+ Kd6 33.Qxg7 was even stronger. I do like Atkins’ move though. It covers the e1 square and thus neutralises any back-rank threats. Meanwhile, White’s threats are still hanging over Black’s (king) position.

30…Qb6 31.Rg3

A little timid. 31.Qh4 was the way to go 31…Kf8 32.Qh8+ Ke7 33.Ng6+

33.Qxg7 Rxe5 34.dxe5 (34.Rh6 Rf5) 34…Rxd1+ 35.Bxd1 Ne4 36.Re3 Qb2 37.Re2 Qa1 38.Re1

was good enough for White to escape I thought but I’d missed 38…Qd4 after which White is in trouble!

33…Kd6 34.Qxg7 fxg6 35.Qxf6 is very promising for White

And now the final mistake from Rubinstein:

31…Rxd4

Rubinstein collapses! 31…Kf8 was the only defence 32.Rxg7 Kxg7 33.Qg5+ Kf8 34.Qxf6 Rxe5 (34…Qc7 35.Qh6+ Ke7 36.Nxf7 wins (36.Qg7 Rxe5 is better for White but not over yet) ) 35.Qxe5 is a clear pawn up for White

32.Rxd4 Qxd4 33.Qxf6 Qa1+ 34.Ke2 Bf3+ 35.gxf3

A sensational win!

1–0

The Yorkshire Post of Tuesday 8th August 1922 reported the game as follows: “Atkins won a fine game against Rubinstein, a most creditable victory for the British master and one which may have an important bearing on the destination of the higher prizes. With good judgement, Atkins allowed Rubinstein to secure some advantage on the queenside having as he believed ample compensation in attack. The finish was complicated and exciting, both players threatening mate in a few moves. Atkins however broke through first and Rubinstein resigned” The Scotsman of the same date noted that “he forced the Polish player to acknowledge defeat with a nod of the head and a wry smile”

Postscript

I found some additional annotations to this game in Tartakower and Du Mont’s “500 Master Games of Chess” .

A small historical correction, before “Dr Winterreise of High Dudgeon Mountain, Switzerland” descends upon you, poring scorn and ridicule: Atkins is not the only player to better Yates’ figure of British Championship wins – Jonathan Penrose won the event 10 times between 1958 and 1969.

Hi Steve, Aaaagh you’re right of course! I’ll correct it as soon as possible. Let’s hope I’m in time! Best Wishes, Matthew

Re: the Hanover 1902 event: there is a nice story of how the FIDE Congress around 1950 proposed to award Atkins the honorary IM title. The Soviet delegate objected on the grounds that he was too weak, whereupon the English delegate pointed out that Atkins had finished ahead of Chigorin at Hanover! The Soviet objection was dropped..

The Soviets later claimed – perhaps credibly – that they had misheard the name and thought the nominee was J M Aitken, the Scottish Champion. who was indeed unworthy of such an honorary title.

Nice story! Surprised they even knew who Aitken was!

I think he had played some Olympiads. Certainly Stockholm 1937 – he won a crushing game as Black against Stahlberg, using the Lasker QGD!.

Hi, thanks for that! If only we could see the game! Best Wishes, Matthew